Kondopoga. Church of the Dormition. Southeast view on the shore of Kondopoga Bay of Lake Onega. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldAt the beginning of the 20th century, Russian chemist and photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography. Inspired to use this new method to record the diversity of the Russian Empire, he photographed numerous historic sites during the decade before the abdication of Nicholas II in 1917.

Prokudin-Gorsky’s final visit to the Russian North occurred in the late Summer of 1916, as the Great War raged in Europe. His special passage during such difficult times was arranged by a state commission to photograph railroad construction to the new port of Murman, built to receive military supplies from the Western allies.

Kondopoga. Tokarsky Pier in Kondopoga Bay with rail tracks (used for loading marble from local quarry). Summer 1916

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyAs part of this journey, Prokudin-Gorsky passed through the small town of Kondopoga and photographed a ramshackle pier used for shipping marble from a local quarry. Oddly, he did not photograph the nearby Dormition Church, one of the most remarkable wooden shrines of the Russian north. Fortunately, I was able to photograph this landmark structure in 2000. Tragically, it no longer exists.

With its ample forests the Republic of Karelia has had numerous monuments of traditional wooden architecture. Although the most widely visited site for these works of traditional art is the museum island of Kizhi, there are distinctive monuments still standing in the region around Kondopoga, located 50 km north of the capital of Petrozavodsk.

Kondopoga. Church of the Dormition. East view. Church destroyed by fire in August 2018. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldKondopoga is now an industrial town with a paper mill that draws upon the region’s ample forest resources. As Karelia’s third largest city (with a decreasing population of just under 26,000), Kondopoga is accessible on the main railroad and highway routes to the port of Murmansk.

The origins of the settlement have been dated to the turn of the 16th century. Its favorable location on a bay near the mouth of the Suna River in western Lake Onega made it a natural site for trade and fishing. During the medieval period Kondopoga was considered part of the territory of Kizhi. All structures, including churches and chapels, were built of pine or fir logs.

Church of the Dormition. East view, upper structure with decorative details. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldKondopoga’s economic significance increased in the 18th century with the discovery of iron deposits that supplied the large metalworking factory established by Peter the Great at Petrozavodsk in 1703. In the middle of the 18th century, extensive marble quarries were developed at the nearby village of Tivdiya, located on a river of the same name. By the 1760s, the marble quarried here could be transported to St. Petersburg via a system of waterways linking Lake Onega with the Neva River.

Church of the Dormition. South facade, upper structure with with chevron pattern containing drain spouts. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldThe growing importance of Kondopoga during the reign of Catherine the Great no doubt contributed to the construction in 1774 of the extraordinary Church of the Dormition. Situated on a narrow cape extending into Chupa Bay (part of Lake Onega), the Dormition Church could be seen over water like a beacon from a great distance.

Church of the Dormition. Southwest view with covered stairway to vestibule. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldTo emphasize this prominent location, the master builders created a tower 42 meters (138 feet) in height. Toward the top of this soaring octagonal structure of notched pine logs was a horizontal band resembling a chevron pattern. These small attached gables not only decorated the structure but also protected it from excessive moisture in this damp region. The bottom of each “V” had a wooden rain spout that collects and expels precipitation away from the log walls.

Church of the Dormition. South facade wth covered stairway leading to main entrance. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldThe church culminated in a tall “tent” tower covered in wooden shingles and crowned with a cupola and cross. Attached to the west of the main structure was an elevated vestibule, or refectory, reached on the outside by a decorated staircase attached to the south façade.

Church of the Dormition. Interior, view east from refectory with massive log pillars supporting ceiling. July 4, 2000.

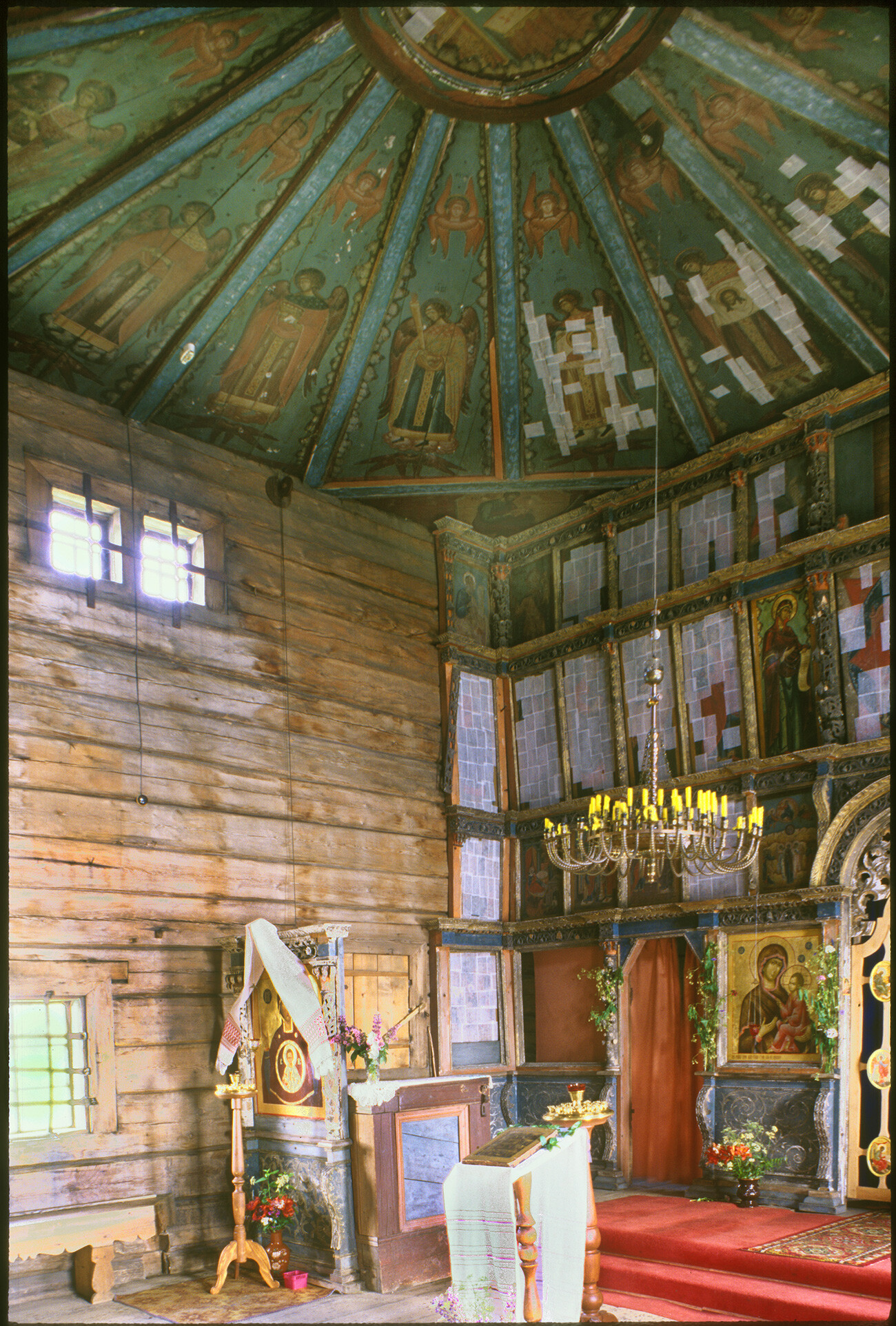

William BrumfieldThe inside of the vestibule created a clean area formed by log walls adorned with icons and painted posts that supported and divided the space. The entrance to the worship space was through a painted doorway that frames a view of the icon screen. Passing from the low vestibule to the tower space creates an unforgettable impression. The tall interior, illuminated by window light, was bounded by an icon screen that concealed the altar.

Church of the Dormition. Interior, portal from refectory to main worship space. Note embroidered cloth protecting Miraculous Icon of the Savior. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldThe interior was covered by a painted ceiling, or “heaven”, a distinctive feature of northern Russian log churches. These "heavens" are an ingenious combination of traditional art and architecture. They consist of a polygonal form segmented by flat beams extending from the top of the walls to an elevated ring in the center.

Church of the Dormition. View east toward icon screen. Icons partially covered with tissue squares during restoration. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldThe beams incline upward and create a frame that is self-supporting between the walls and the ring where they meet at the center. The painted panels are in the shape of narrow triangles and are laid upon the inclined frame without fasteners.

Church of the Dormition. Painted ceiling called "nebo" (heaven) with depictions of archangels, one of whom holds Miraculous Icon of the Savior. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldThe number of triangular panels can vary, but, in the Dormition Church, there are 16. They depict angels, including the primary archangels. The ring in the center contains an unusual image of Christ as a priest standing at the altar.

Church of the Dormition. Interior, view northeast with icon screen and painted ceiling. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldDuring World War II, Kondopoga was occupied from early November 1941 until the end of June 1944 by Finnish forces, at that time allied with Germany. Although the town’s industry was ransacked, the Dormition Church – located on the outskirts – was untouched. A thorough study and conservation of the church was undertaken in the 1950s.

Church of the Dormition. Southeast view on the shore of Kondopoga Bay. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldIn the 1990s, the interior of the Dormition Church was again the object of careful restoration, even as the church was returned for active parish use. The complex balance between parish use and the need to preserve this unique historic structure (remote from the main housing districts) led to the construction of a new, more spacious wooden church, completed in 2009 and dedicated to the Nativity of the Virgin.

Vikshitsa. Chapel of St. Alexius of Rome. Cemetery shrine (not extant) above Lake Pertozero. Summer 1916

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyDespite structural concerns for preserving such a tall structure located near a body of water, the Dormition Church continued to receive visitors until disaster struck. On August 10, 2018, the church burned to the ground in a senseless act of arson. All the historically valuable icons and ceiling paintings were lost in the fire. Preliminary plans to rebuild the church have been approved on the basis of careful documentation before the fire, but a copy will never equal the artistic majesty of the original.

Although Prokudin-Gorsky did not photograph the Dormition Church, he photographed Karelian chapels that resemble shrines still existing in the Kondopoga area. Among them is the Chapel of the Kazan Icon of the Virgin at the village of Manselga. With a bell tower over the entrance in the west, the Kazan Chapel follows a typical form for wooden chapels in Karelia during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Manselga. Cemetery & Chapel of Kazan Icon of the Virgin, southwest view. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldA distinctive expression of this traditional form is the late 18th-century Chapel of the Three Prelates, originally at the village of Kavgora in the Kondopoga region but subsequently transferred to the museum on Kizhi Island.

Kizhi. Chapel of Three Prelates, originally built at village of Kavgora. July 13, 1993

William BrumfieldThis intricately crafted structure, with decorative carved end boards, culminates on its west end with a tall octagonal bell tower. Like the Dormition Church, it has an elevated covered stairway to provide access over the high snows of the Karelian winter.

Martsyalnye Vody. Church of Apostle Peter, northwest view. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldThe most unusual variation of the traditional wooden chapel in the Kondopoga region is the diminutive Church of St. Peter at Martsialnye Vody (a word play on the Russian for “mineral waters” and the Roman god Mars).

Martsyalnye Vody. Church of Apostle Peter, northeast view. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldMartsialnye Vody was founded by Peter the Great in 1719 at the site of mineral springs and is considered Russia’s first spa. Peter visited Martsialnye Vody on four occasions between 1719 and 1724.

Martsyalnye Vody. Caretaker's house at mineral springs. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldLegend has it that the Church of St. Peter was built to the tsar’s own design, which combines traditional elements with a baroque dome over the main space.

Martsyalnye Vody. Late 19th-century water pavilion. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldAlthough the spa fell into decline after Peter’s death in 1725, it was revived in the late 19th century and again in 1964.

Koncherzero. Log house with balcony. (House originally had barn attached at the back.) July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldThe Martsialnye Vody spa functions to this day, with the Church of St. Peter preserved as a link to the time of Peter the Great.

Podgornaya. Chapel pavilion over sacred spring. July 4, 2000

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century, Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916, he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France, where he was reunited with a large part of his collection of glass negatives, as well as 13 albums of contact prints. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century, the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986, architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox