Ever heard of the Itelmens, the Native Americans’ Kamchatka relatives?

About 100 people are dancing on green grass to the rhythmic beat of a tambourine. They are surrounded by spectators, who are filming them on their phones. The “ringleader” in the center, a nearly two-meter-tall shaman with long ink-black hair and broad shoulders, has a mic. After his signal, this mass of people in folk costumes begin to sway from side to side, like a sea wave.

This is an Itelmen ritual holiday called ‘Alhalalalai’, which now brings together all indigenous peoples of the north every year. “I won’t be surprised if they will soon proclaim that Alhalalalai is their holiday,” says Oleg Zaporotsky, a local Itelmen, somewhat jealously.

Incidentally, all indigenous peoples of the Russian north are genetically related to Native Americans, but the Itelmens consider themselves to be their closest relatives. At least, they are not trying to hide, forget or dispute this fact. A related Indian tribe from Canada once presented them their costumes, which the Itelmens now wear with much pride. Yet, the Itelmens are little-known in Russia. Even less so than the Evens or Koryaks. If the indigenous peoples of the north had their own popularity rating, the Itelmens would be close to the bottom of the list, together with the Ainu, a people whose existence has been officially denied in Russia for the past 41 years. Had it not been for Alkhalalalai, the Itelmens would have been forgotten by everybody, except photographers.

The holiday includes a dance marathon: 15-16 hours of wild energy. The main rule is that you cannot stop. The latest record - 17 hours and 5 minutes of nonstop dancing – was set by Andrey Katavynin (‘Koritev’) and Darina Etante (‘Mengo’).

A dancing people

The word Itelmen means “living here”. They are one of the indigenous peoples of Kamchatka. However, by the second half of the 19th century - as a result of military clashes with Russians and Cossacks - they remained only on the western coast of the peninsula.

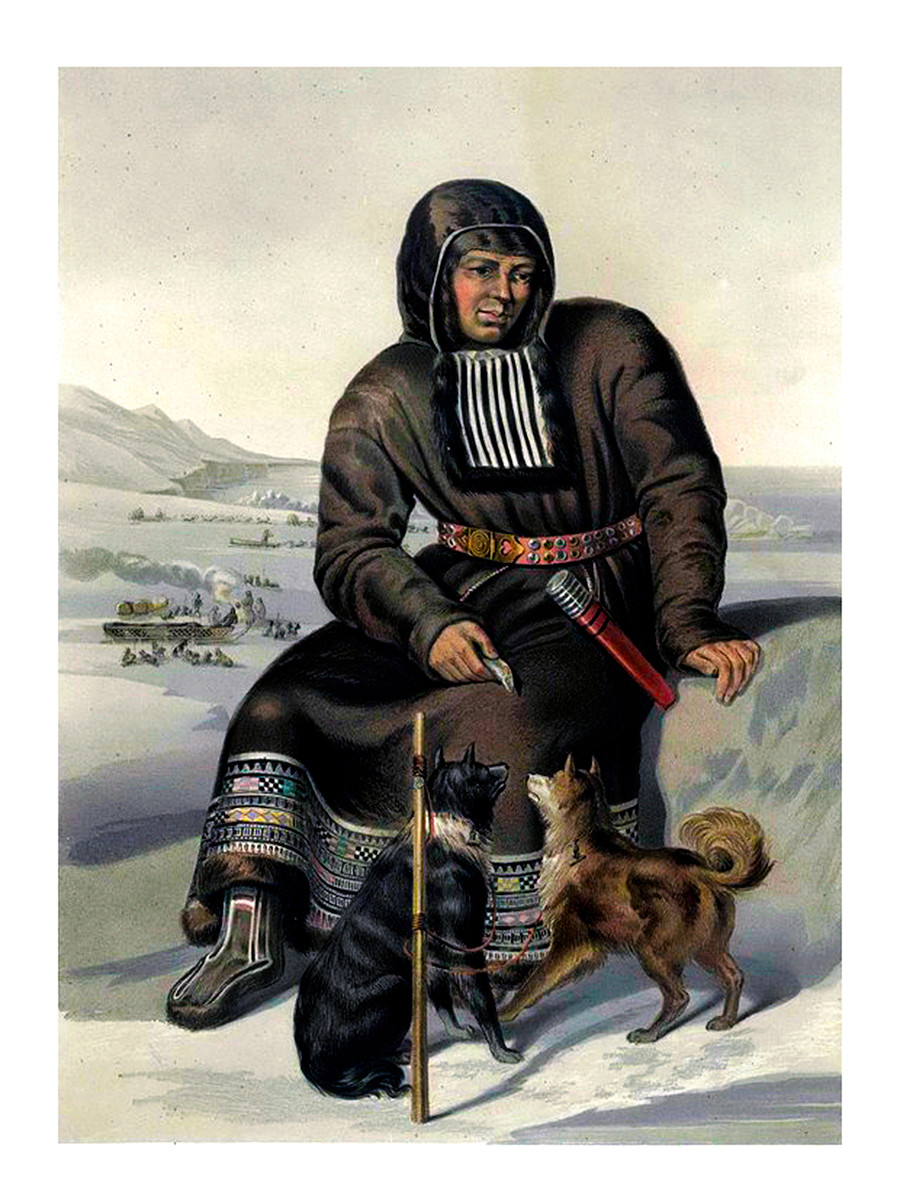

Kamchadal (Itelmen) 1862

Public DomainNow, the Itelmen population is concentrated in the small village of Kovran in Kamchatka’s Tigilsky District. To reach it from Moscow, you need to take an eight-and-a-half-hour flight to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, then take a 10-hour bumpy ride by car to the village of Esso, then hop on hour-and-a-half flight by helicopter to the village of Ust-Khairyuzovo, followed by a 40-minute drive in an all-terrain vehicle through the tundra along the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk. “Make sure you do it at low tide, otherwise you may be washed away into the sea - there have been such cases here,” experienced travelers warn.

“Until the age of nine, I lived in Kovran. In 1997-98, there were about 200-300 Itelmens there, as far as I can remember. Then, we moved to the village of Esso, where my relatives live now. There are few Itelmens there, maybe 30 people,” says Natasha (name has changed). She herself has moved to St. Petersburg, “because there you can develop and study”, and works as a masseuse. On Russia’s most popular social network, VKontakte, the Itelmens’ group has only 35 members, including Natasha. According to the 2010 census, there are just 3,093 people in Russia who self-identify as Itelmen.

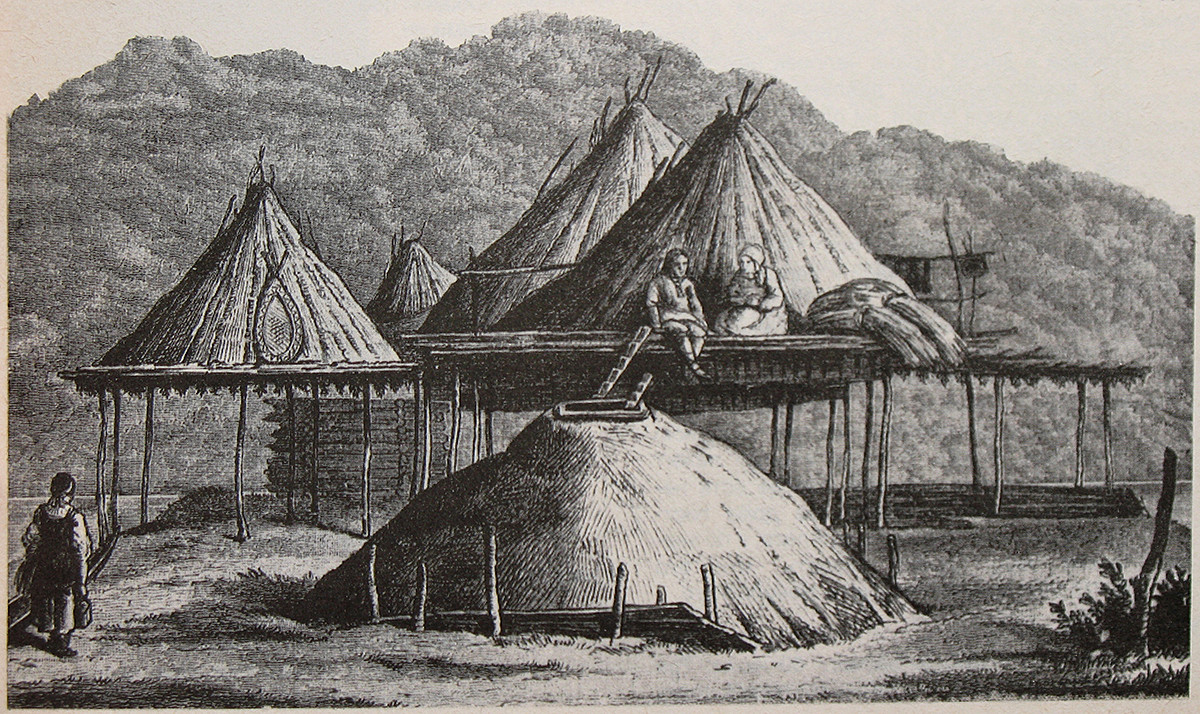

Kovran

vevechkh/youtubeThe first time a census and a thorough study of this indigenous people was conducted was in the 17th century. At the time, there were almost 17,000 Itelmens. In winter, they lived in semi-dugout yurts, and in summer, moved closer to the river and lived in yurts on stilts. The Itelmens believed in spirits, were animists, and according to ethnographers, in ancient times practiced sky burials, burying their deceased in the hollows of trees.

The process of assimilation with the Russian population was quite active: in the 18th century, many Itelmens had already moved into Russian huts. In the 19th century, they converted to Christianity and were given Russian surnames based on the names of priests and church wardens in their parishes. Their traditional way of life, which revolves around fishing (Itelmens are born fishermen), exists to this day, although very few people maintain it. It is only legends, known by every Itelmen child, and centuries-old Itelmen beliefs that continue to constitute the Itelmen reality. For example, the belief that one should not fear death or condemn suicide. The Itelmens believe that when life ceases to bring joy, a person can make the transition to the “upper world” themselves.

Serious people – always with dogs

“In the 1960s, life was pretty hard. I was the oldest of five children,” Oleg Zaporotsky recalls. “There were a lot of household chores. We had to look after our dogs and spent all summer holidays preparing food for them. Everyone kept dogs - if you did not have a dogsled in your backyard, you were considered a frivolous person. I remember walking through the village and a neighbor would open a pit with sour fish for dogs - the smell would envelope the whole neighborhood, disgusting! Although now, to be honest, I would breathe it in with pleasure,” he continues.

As he grew older, the list of chores grew too. On weekends, Oleg went to the forest to get firewood, and every day, if there was no snowstorm, he brought the firewood home from the forest on a dogsled. When planes began to fly to neighboring Ust-Khairyuzovo, he went to meet Kovran passengers there, sometimes at night. “Father would tell me: ‘Get ready and go.’ And I would ride 20 km at night, pick people up and, in pitch darkness, bring them to their home village.”

Natasha is too young to have experienced that lifestyle first-hand. “I live like any ordinary modern person. Although, sometimes I do feel like taking a trip in a kayak (previously, the Itelmens sailed in boats made of animal skins), or weaving dried nettles (called lepkha). That’s about it. And I sometimes read Itelmen fairy tales to my friends.”

Natasha says that even in Kamchatka, in their native land, at some point, the Itelmens stopped feeling at home: “After moving to the village of Esso the Evens were not very friendly, because it’s kind of their village, since the majority of the population are Evens. I was only 12-13 years old when, as I was lining up at the store, I would hear: ‘There are far too many of these newcomers here’.”

Roots

At some point, the Itelmens began to rapidly lose touch with their roots. In 1989, only some 20 percent of Itelmens named the Itelmen language as their native tongue. Furthermore, its speakers were mostly aged 50 and above. Natasha’s family had an direct connection with the Itelmen language - her grandmother was a linguist, and in the 1980s, began working on the first ever Itelmen textbook – however, even their family began speaking Russian, only occasionally using some Itelmen words.

Natasha says she personally does not know any people who speak Itelmen, know the language or at least its alphabet. She adds: “Most of the residents of our village of Kovran just drank themselves to death. Alcoholism is a real problem.”

It must have been this cultural decline, coupled with their dwindling numbers, that prompted the Itelmens to take responsibility for their own survival. There was little help from the state. In 1989, the Itelmens were among the first in the country to create their own public organization - the Tkhsanom Council for the Revival of Itelmens of Kamchatka, headed by Oleg Zaporotsky. They set up their own dance troupe, which gained popularity and toured in Europe, and turned the local Thanksgiving holiday, Alhalalalai, held at the foot of a sleeping volcano, into a northern brand and the core of their ideology. “I think this is our main achievement,” Zaporotsky says.

Even their forgotten ethnic cuisine is now being revived. “I am very glad that my father made me learn it all. I didn’t want to, I thought I would never have any use for it. Indeed, the ability to cook seal fat, yukola [dried fish or deer meat] and sour fish heads did not seem particularly appealing!”

Last year, according to local media reports, the title of ‘Itelmen of the Year’ went to Lidia Kruchinina, the head of the dance ensemble, who had won first prize in an haute couture competition of folk costumes in Moscow - after submitting stage costumes made of fish skin.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox