Why are Slavs so divided?

While Slavs are close genetically, disputes between them tend to be really hot.

Irina BaranovaWhat does it mean to be a Slav? The question is tricky, as this group contains dozens of ethnicities (and from 300 to 350 million people). Slavs live everywhere from Germany to Kazakhstan and Russia’s Far East – add to this migrants and you’ll find Slavs basically anywhere on Earth. It is difficult to maintain anything common if you are this dispersed.

Nevertheless, there are some options. For instance, the Slavorum page, dedicated to the complications and peculiarities of Slavdom, lists the most common Slavic commandments in memes: from having loving but food-obsessed older relatives (“Your mom tells you you’re too skinny even though your 30 pounds overweight) to alcohol tolerance (“Your 15 year old sister can out-drink any American guy”). And, if you’re Slavic, you ALWAYS take off your shoes while inside someone’s home.

But there is one feature that cannot be applied to Slavs – the idea that Slavic people are all alike and should always love each other. In fact, throughout Slavic history, unfortunately, the opposite is true. Why is that?

From Prague to Vladivostok

Girls with children during the ancient Rusal folk festival in Belarus.

Vladimir Smirnov/SputnikFirst, it is important to remember how widespread Slavs are. While, according to historians, they originated from the relatively small area between the Elbe and the Oder rivers in the west and Dnipro and Dniester in the east, now Slavs are spread all over Eastern Europe and (so far as Russians are concerned) Northern Asia.

There are three subgroups to Slavs: Western Slavs (Czechs, Kashubs, Moravians, Poles, Silesians, Slovaks and Sorbs), Southern Slavs (Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes) and Eastern Slavs (Belarussians, Russians and Ukrainians).

World Cup 2018 volunteers take a photograph next to a mural showing the national flags of Russia and Serbia and the message "The Russians and the Serbians are Brothers Forever" in central Kaliningrad, Russia.

Vitaly Nevar/TASSThey share the same heritage – linguistically speaking. As Oleg Balanovsky, a researcher from the Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, emphasizes, “Slavs are those who speak languages that had the same root, the proto-Slavic language.” That’s it. Common linguistic roots – and nothing more.

Troubled history

Czechs protesting against the Soviet invasion in the late 1960s. Such episodes definitely didn't help to establish Slavic unity.

Central Intelligence Agency“Once Slavs were an ethnicity but for many centuries they have been only a language family,” archeologist Leo Klejn agrees in an article bashing theories of ‘the special Slavic DNA’. “There is no such thing as a Slavic race, Slavic political unity, a specific Slavic culture. Now we don’t have even a Slavic language – only different languages close to each other.”

Speaking of political unity – it’s hard to imagine one given the fact that Slavic nations had lots of conflicts and went to war with each other from time to time. Russian-Polish relations, for instance, are tarnished by the three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth between Russia, Austria-Hungary and Prussia which happened in the 18th century, ending the existence of sovereign Poland for 123 years.

Add to this the Soviet-Polish war of 1919-1921 and 1939 when the USSR and Nazi Germany de-facto divided Poland – and you’ll understand that Poles get quite angry when they’re mistaken for Russians. Even though they are really close in terms of looks and genetics, Balanovsky says – only Belarussians and Ukrainians are closer to Russians genetically.

Of course, Russia is not the only Slavic country with complicated relationships with its Slavic neighbors. There is no love lost between the former Yugoslavian nations (especially Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs) either, as it’s been less than 20 years since the ending of the wars of the 1990s, which followed Yugoslavia’s dissolution. It seems that nations tend to have most problems with neighboring states – no matter how close they are genetically and linguistically.

Attempts to unite the Slavic world

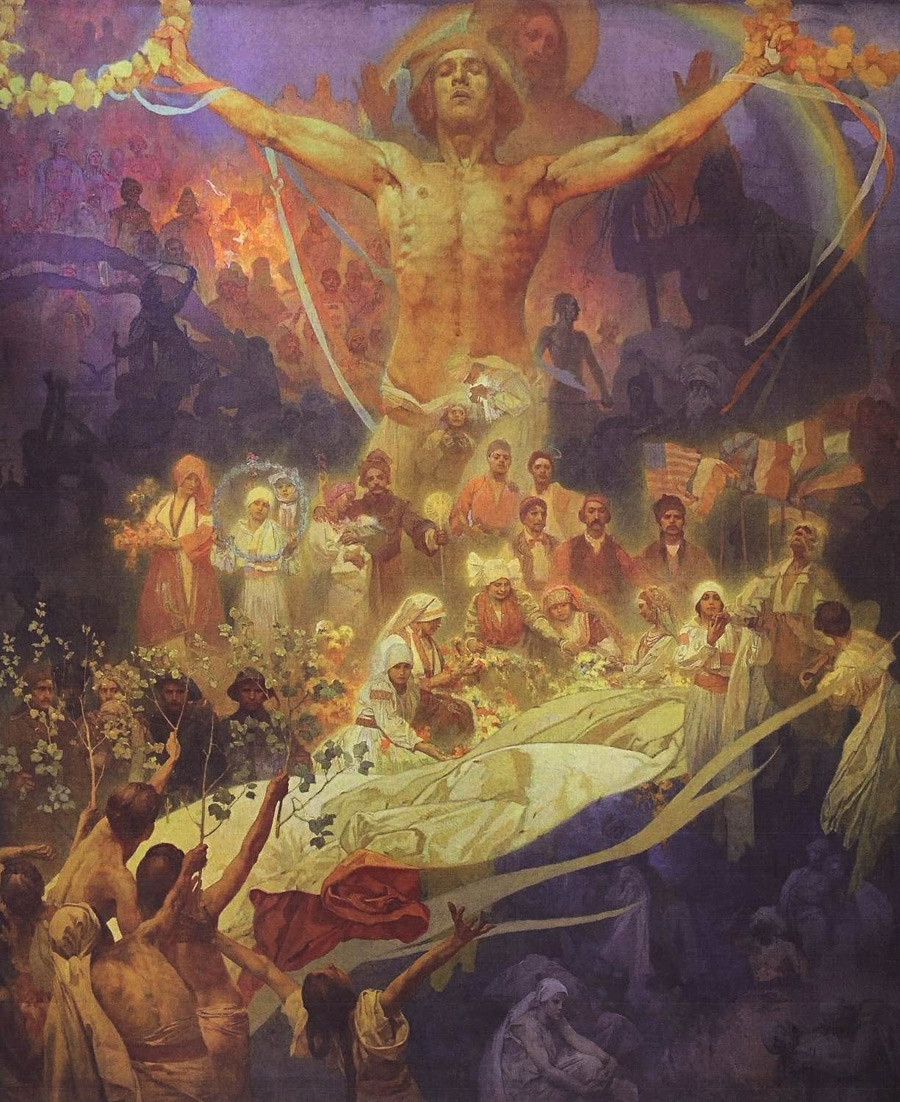

"Apotheosis of the Slavs history" by Czech artist Alfons Mucha (painted in 1929). Mucha could only dream of the Slavic unity - and the situation didn't change to a great extent.

Prague City GalleryOn the other hand, there have been those who have tried to make Slavs overcome their differences and stand together. Pan-Slavism was a popular ideological movement in the late 18th-early 19th century, as Southern Slavic people were seeking independence from Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire and cherished the idea of an integral Slavic world.

In the 19th century Russia, many supported the cause, including the famous author and great Russian patriot Feodor Dostoevsky. “Russia cannot betray the great idea… which she has been following steadily. This idea is the all-unity of Slavs… not as seizure or violence but as a service to humanity,” Dostoevsky wrote in his diary in 1877, when Russia was fighting against the Ottoman Empire along with the Balkan Slavs. That war de-facto returned independence to Bulgaria and led to Serbia enlarging its territory.

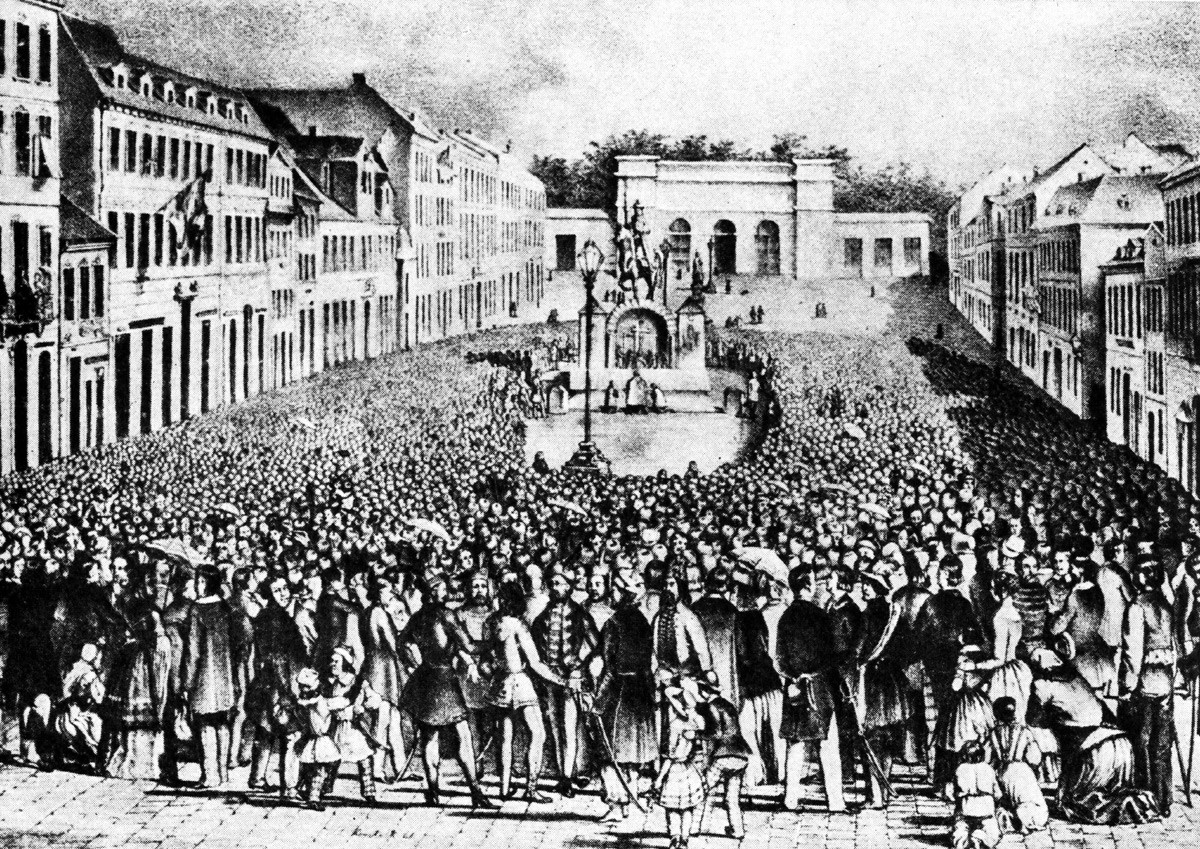

Prague Slavic Congress, 1848

Legion MediaBy that time, the Slavic movement already had been a thing: since 1848, when Prague hosted the first Slavic Congress, it had a flag (blue-white-red – these colors can be now seen at flags of many Slavic countries) and a hymn (“Hey, Slavs!”). In Russia, the Slavophile doctrine was an important element of political thought in Russia: the Slavophiles denied pro-Western views and, much like Dostoevsky, believed that Russia should lead the Slavic world, truly Christian and opposed to a morally degenerate Europe.

As we can see, that didn’t happen: political disagreements prevailed. WWI and the revolutions of 1917 that turned Russia into a Socialist state also resulted in the Slavic factor not playing a crucial role in what followed. As for now, Slavs remain divided politically – but it doesn’t prevent them from being friendly and hospitable to each other on a personal level.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox