How did Russians use social networks in the 19th century?

Social networks allow us to share our lives and thoughts with our circle of friends and acquaintances. While Ancient Roman aristocrats had daily morning, lunch and evening receptions for guests, the Russian nobility used to pay each other formal visits. For example, newlyweds were obliged to visit all their relatives on both sides; and when a person fell ill, he still had to receive visitors wishing him good health. Even more, all these visits were to be paid back.

P. Fedotov. "Aristocrat's Breakfast (An Unwanted Visitor)". 1849-1850.

Tretyakov Gallery“On Thursday at 6 p.m. Maria Ivanovna hopped in the carriage and went on visits, with a schedule in her hand. That day, she paid 11 visits, on Friday before dinner - 10, after dinner - 32, on Saturday - 10 more; 63 in total, and she left some 10 visits for her closest ones on Sunday.”

After a member died, the family had to accept visits of condolence. Martha Wilmot, an English woman living in early 19th century Russia, expressed her disdain for this tradition, but was told that, “had the widow not sent the announcement [about her husband’s death], society would have condemned her as disrespecting her husband’s memory, people would question the sincerity of her grief, she’d gain a bunch of enemies, gossip would be relentless and eventually, nobody would visit her house.” Speaking in Facebook terms, the widow would have been banned from the network.

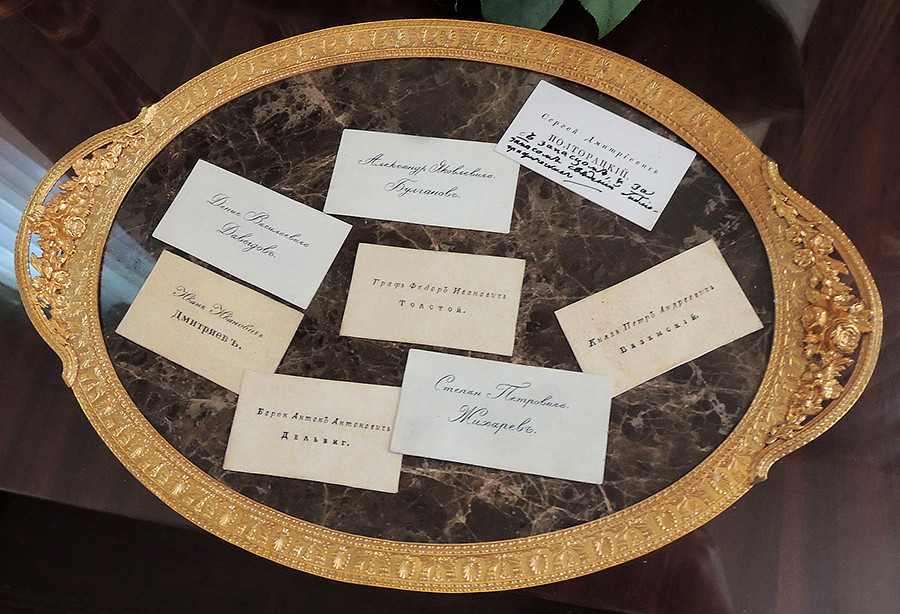

But you didn't always have time for a visit. So, there was another way - business cards, which became popular starting in the 1830s. When paying a visit to a person currently not home, one could leave his or her card, or send it with a servant (you couldn’t use servants to bring cards to people superior in service or with superior titles; that would be too boorish).

Personal business cards of the 19th century.

ShakkoAn array of cards on your coffee table showed your social circle and the people you were acquainted with - a kind of Facebook friend list. “Some oddballs are paying lucrative sums to doormen and valets in noble houses, so that the doormen bring them the rich people’s cards that were sent to their noble masters. Such a character would tuck these indisputable proofs of splendid acquaintances behind their mirror to show their less splendid friends that they have connections in high society.”

Tinder

Social ties could be very useful for a young man looking for a bride. But if one didn't have many acquaintances, he could go and find a match at unofficial dating sites. Just like Tinder, these sites offered the opportunity to pick matches from a random set. In Moscow, the families of merchants and petty bourgeoisie took their girls out on the feast of the Baptism of the Lord: “The entire embankment was filled with girls in expensive winter outfits. In front of them, young merchants in fox coats and high hats strutted, looking buoyant and cheerful…” Female matchmakers were close at hand to assist the choice.

The "Small" Church of Ascension in Moscow. This was one of the churches where noblemen could come looking for a bride.

Nikolai NaidenovThe nobility, of course, wouldn’t look for fiancees on a winter embankment. Apart from the known matchmakers that they used, noble families had certain churches one could visit to look for a bride. A young man had to show up at such churches and pray, all the while scanning the place for a girl he liked. As soon as he saw her, his gaze would be intercepted by an attentive aunt, who’d quickly tell him the girl’s last name and the appropriate time to visit - and this might be a match.

Messengers

A scene from the film-opera Eugene Onegin (Lenfilm, 1958).

SputnikMessengers are a great way of communicating with each other discreetly when there could be eavesdropping in the area. Young people in the 19th century desperately needed a smartphone at a ball or during an evening reception. As a girl, you can’t flirt with a guy when a bunch of nannies and aunties are insisting on your good manners. So, they invented a secret language which utilized gestures with hand fans and the “language of flowers.” Of course, many aunties understood this language, too. But communicating discreetly like this was the only socially acceptable way. A noble woman or a man couldn’t possibly discuss love or private matters vocally.

An admirer could send his love a bouquet that could read like a message. Austrian rose meant “big love;" Damask rose - “shy love;" while sending yellow roses meant that you suspect infidelity. Viola tricolor - “remember me;" ocimum - “I hate you;" brown geranium - “I’ll meet you;" laurus - “I’ll be true until I die;" and so on. Combinations of flowers could convey an elaborate message, and the choice of flowers spoke a lot about the admirer’s taste and amount of wealth.

During an evening reception, young ladies utilized hand fans to convey messages, a fashion that came from Spain and France. To express affection, a woman pointed at a man with the upper end of a fan, while the other way around meant disdain. Girls repeatedly opening a fan expressed her approval, while holding the fan open meant passionate love.

Some gestures conveyed straight messages: tapping the hip meant “follow me;" touching the left ear with an open fan - “we’re being watched;" folding a fan slowly with the left hand meant “come, I’ll be delighted.” This “fan language” became so popular, that words “to wave [a fan]” for a short time denoted “to flirt”.

If you’d like to learn more about 19th century Russia, check our article on dining rules or the Afghanistan spy story. For more fascinating details, look into the biography of the Russian nobility’s most daring swashbuckler, Fyodor Tolstoy.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox