Marshal Georgy Zhukov, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky in Berlin, 12 June 1945.

Imperial War Museums/Getty ImagesThe Red Army began the last year of the war fighting heavy street battles in Budapest and getting ready for the liberation of Warsaw and for an offensive in East Prussia - the location of Königsberg, one of the most important cities of the Third Reich.

Badly shattered in the battles of 1944, the enemy still retained a relatively high combat readiness. Despite the loss of vast territories, important industrial regions and almost all of their key allies, the Germans were prepared to fight to the bitter end.

Soviet toops in East Prussia.

Sergey Kosyrev/SputnikOn January 12, a Soviet offensive was launched along the principal line of attack - through Poland. The Red Army had approached the outskirts of Warsaw back in the Summer of 1944 and then took a long operational pause. On January 17, 1945, with the support of units of the Wojsko Polskie allied with the USSR, the Red Army liberated the city.

As the ‘Vistula-Oder Offensive’ gained momentum, Soviet troops advanced up to 500 km westwards, routed 35 German divisions, liberated a considerable part of Poland and, in early February, reached the distant approaches to Berlin. The Wehrmacht command had to hurriedly transfer formations from other sectors of the front, including the Western Front, to defend the German capital.

“The appearance of Soviet troops 70 km from Berlin utterly astounded the Germans,” recalled Marshal Georgy Zhukov. “When a forward unit (of the 5th Shock Army) burst into the town of Kienitz, German soldiers were casually walking around the streets and the local restaurant was full of officers. Trains on the Kienitz-Berlin line were running on schedule and communication lines were operating normally.”

Soviet soldiers fighting in Warsaw's oustkirts.

Alexander Kapustyanov/SputnikThe large-scale battle for East Prussia, which started at practically the same time as the Vistula-Oder Offensive, proved costly for the Red Army. The Wehrmacht had managed to turn this strategically and ideologically important region into little short of an impregnable fortress and, by the end of the first month of fighting, many Soviet divisions only had a little more than half their manpower still operational.

Eventually, the enemy grouping was fractured into parts and pinned against the Baltic Sea. The Soviet navy was unable to fully blockade the Germans, however, and this allowed them to maintain a ferocious resistance almost until the beginning of May.

Königsberg, assailed from several sides by the Red Army, fell on April 9. More than 90,000 German soldiers and officers were taken prisoner. Otto Lasch, the commandant of the city, declared during his interrogation: “It was simply impossible to anticipate that a fortress such as Königsberg could fall so quickly. The Russian command planned the operation well and implemented it admirably… The loss of Königsberg is the loss of a major fortress and Germany’s stronghold in the east.”

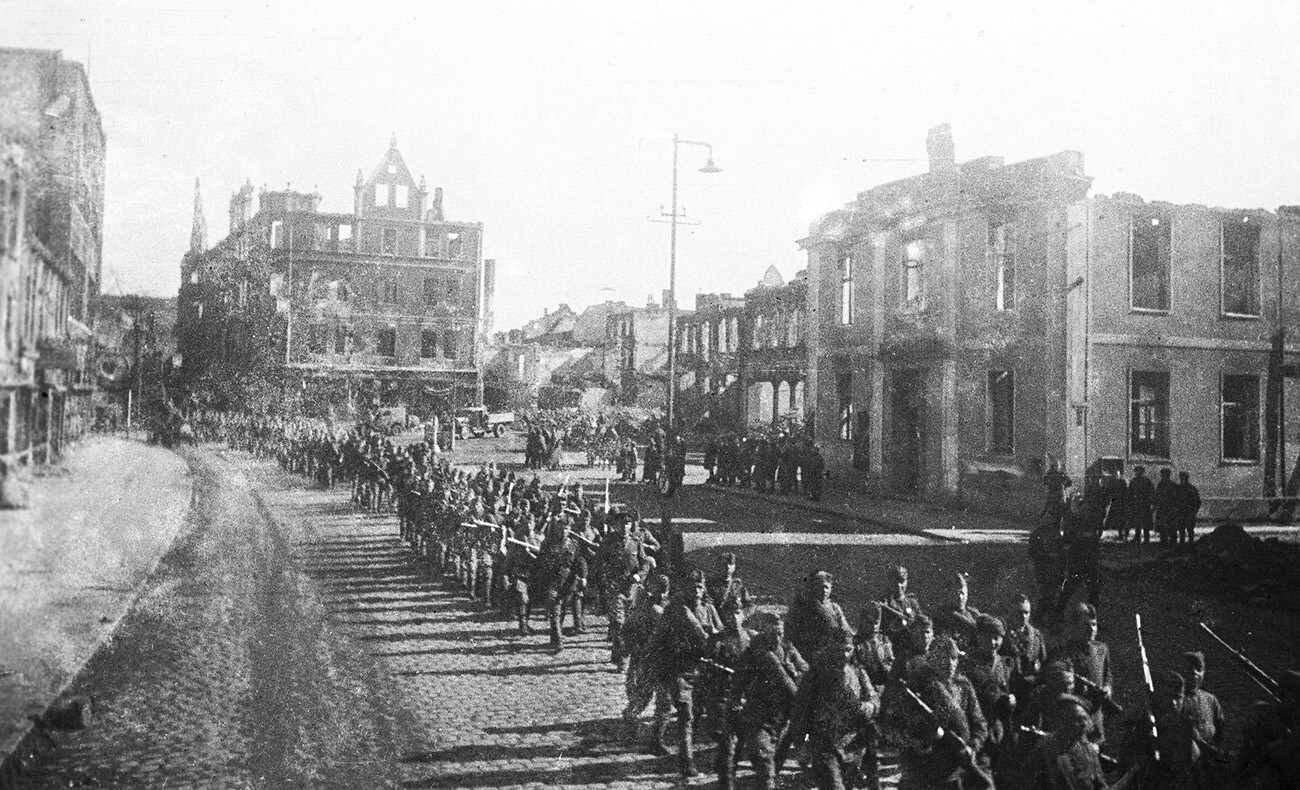

The Red Army entering Königsberg.

Nikolay Maksimov/SputnikIn order to allow the troops of Zhukov’s 1st Byelorussian Front to advance unimpeded towards Berlin, their flanks needed to be secured. The German grouping in Eastern Pomerania was defeated in February-April and, on March 31, the strategically important port of Danzig was taken.

On the southern axis, in turn, a bitter battle for Budapest ended by mid-February, after many months of fighting. With the loss of the Hungarian capital, German troops in Yugoslavia were in danger of finding themselves cut off, while the Red Army now had the opportunity to step up its advance towards Vienna and Prague.

“The going was tough,” is how tank crewman Nikolai Vershinin described the fighting in Budapest. “You would be moving forward in your tank and you’d stop at a corner and blast away at buildings where firing positions had been located by our infantry. To be quite honest, we tried to aim in such a way as to demolish the houses as much as possible, because otherwise it was impossible to get past. All the street battles merged into one endless and monotonous round of fighting… I have to say that we did not like the Magyars, because they fought even more doggedly than the Germans. The latter could still pull back as the end of the war approached, but the Hungarians fought to the bitter end.”

A Soviet gun crew keeping up fire in the streets of Danzig.

SputnikOn the morning of March 6, German and Hungarian troops began their last large-scale offensive of World War II. ‘Operation Spring Awakening’ was conducted in the area of lakes Balaton and Velence and aimed to push the Red Army back from the last major oil deposits in western Hungary and Austria.

“Our regiment suffered colossal losses at Lake Balaton,” recalled Lt. Eduard Melikov of the 877th Artillery Regiment. “Two-hundred German tanks advanced simultaneously against our division’s positions and our howitzers were firing at point-blank range… There was very heavy fighting. The regiment did not suffer so many losses of men in the whole war as it did in Hungary.”

By March 15, however, the offensive had already run out of steam - the 400,000-strong grouping managed to advance no more than 30 km beyond Soviet positions. The 6th SS Panzer Army, which was the spearhead of the principal attack, lost more than 250 tanks and self-propelled guns and ceased to represent any kind of meaningful fighting force.

German equipment abandoned near Lake Balaton.

Evgeny Khaldey/SputnikThe day after the collapse of ‘Operation Spring Awakening’, Soviet troops themselves went on the offensive and started a swift push towards Vienna. Fierce fighting for the Austrian capital started on April 6 and lasted around a week.

“The Germans abandoned industrial plants and factory buildings quickly because between them lay open ground unsuitable for defense,” recalled General Ivan Moshlyak, commander of the 62nd Guards Rifle Division. “But, in the narrow streets and alleys, they put up strong resistance. The automobile plant was perhaps the exception. The Nazis were dug in behind a railway embankment inside the cellars of the factory building and their machine-gun fire prevented our assault groups from advancing… The men of the division liberated one house after another, one street after another, pinning the Germans against the Danube.”

After taking Vienna, Soviet troops continued their westward push as far as the River Enns, where, on May 8, they met up with the Americans.

Soldiers of the 4th Guards Army running up the ship's ladder under cover of a smoke-screen during a battle for the Danube Channel.

Vladimir Galperin/SputnikThe Soviet command concentrated forces of over two million men for the offensive against the capital of the Third Reich. They faced 800,000 soldiers of the Wehrmacht, SS and the Volkssturm home guard militia.

After breaking through several defensive enemy lines, Soviet troops tightly encircled Berlin on April 25. Fierce street battles began, and the closer the Red Army approached the center of the city, the more ferocious the fighting became.

The battle for the Reichstag broke out on April 30, the day of the Führer’s suicide. “Our tanks fired at the building at point-blank range and inside it was already a shambolic mayhem of people - our men and the Germans,” recalled infantryman Yakov Fadeyev. “Elite SS troops and Hitler’s personal gendarmerie were defending the Reichstag building against us. They were armed to the teeth and fought to the death. Battles raged for every brick and men fired off their weapons, hacked at each other with trenching shovels and strangled one another with their bare hands…”

A red flag was raised above the Reichstag on May 1, even though fighting continued until evening. The Berlin garrison capitulated the following day.

Soviet troops near the Reichstag.

Ivan Shagin/SputnikThe taking of Berlin did not signify an immediate cessation of hostilities. The new German government headed by Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, which was based in the town of Flensburg in northern Germany, commanded large forces in Czechoslovakia and Austria. The Nazis still hoped to reach an agreement with the Western allies and form a united front with them against the Russians or, as a last resort, to surrender these regions to them before the approach of the Red Army.

On May 6, the troops of Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front mounted a push towards Prague, which had been swept by a rising of the local population. Tank formations traveled day and night, covering up to 50 km per day. Within a short space of time, they had broken through to the rear of Army Group Center.

On May 8, Soviet troops took Dresden and, on May 9, they entered Prague. “The Czechs gave us a splendid reception,” noted tank crewman Vasily Moskalenko. “Small boys ran up to our tanks with pails of cold water, as if to order. For us, weary from our extended advance, it tasted like honey. They went up to each tank and regaled us. The lilacs were already in blossom and lilac flowers were presented to each tank crewman by the armload. People, both young and old, screamed with joy and grabbed our hands. We kissed and embraced.”

Prague townsfolk welcome the Czechoslovak corps soldiers who together with the Red Army liberated the country from the Nazi occupation.

SputnikEven after Germany had capitulated, a certain number of German troops refused to lay down their arms. They attempted to fight their way west, in order to surrender to the Americans and British.

Around 200,000 German soldiers were still occupying a part of Soviet territory. The so-called ‘Courland Pocket’ had been formed in October 1944, when Soviet troops broke through to the Baltic seaboard in the area of the city of Memel (Klaipeda), cutting off the forces of Army Group North in western Latvia.

Pinned against the sea, the enemy resisted right up to May 9. “We first realized that the war was over from the Germans,” is how marine infantryman Pavel Klimov recalled that day. “We were proceeding along the shore and couldn’t understand the commotion and jubilation along the German trenches. It turned out that they had learned that the war had ended. We realized from the fireworks and the firing in the air that it was over… There was a lot of joy.”

German military equipment seized by Soviet forces after the defeat of the Wehrmacht's Army Group Courland.

Leonid Korobov/SputnikUnder agreements reached at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Soviet Union pledged to enter the war against Japan 2-3 months after the defeat of Nazi Germany.

The upshot was that on August 9, 1945, the Red Army dealt a crushing blow to Japanese troops deployed in Manchuria. After crossing arid steppes, the Gobi desert and the Greater Khingan mountain range, in the course of a week and a half, it penetrated hundreds of kilometers into enemy territory, dismembered the enemy forces into a number of isolated groupings and surrounded them.

“By August 19, 1945, the question of who would come out on top had already been decided,” recalled Valentin Rychkov, a sailor. “Our three fronts, commanded by Marshal Vasilevsky, essentially smashed the much-vaunted Kwantung Army and it, basically, began to surrender. But, some of the Japanese units, particularly those led by fanatical commanders, put up a desperate fight. So in spite of the fact that the war was about to end, sailors and ground troops sustained galling losses.”

Pressed on all sides, Japan finally surrendered. The instrument of capitulation was signed on the deck of the American battleship, the USS Missouri, in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945 - marking the conclusion of the most terrible armed conflict in human history.

Japanese troops surrender.

Evgeny Khaldey/SputnikIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox