Head of the Russian Orthodox Church (Patriarch Kirill) meets Head of the Catholic Church (Pope Francis) for the first time ever. Cuba, 2016

Maurix/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesThe year 1054 is considered the official date of the Great Schism. But the disagreements between Western-oriented Christianity led by the Pope in Rome, and Eastern-oriented Christianity led by Constantinople’s Patriarch, began even earlier.

At that time, Rome (which controlled most of Western Europe), and the Byzantine Empire (which controlled most of the Near East) had their own Christian churches. The situation was even more complicated in the East, where regional and autonomous churches existed for the provinces of Greece, Palestine, Armenia, Georgia, Egypt, Syria, and also Ancient Rus’. Considering the isolation and difficulty in communication over 1,000 years ago, we can imagine how different these churches were from each other.

West and East had already definitively split in terms of culture and tradition (and even climate), and had completely different worldviews and societies. In short, they didn’t understand each other in nearly every possible way. This resulted in a confrontation so heated that the Churches imposed anathemas on each other that were lifted only in 1965.

It’s clear that the differences in the views of both Churches had a deep spiritual and worldview basis, which theologians and scholars are still researching. Let’s take a look at the formal differences that played a role in the historic split in 1054.

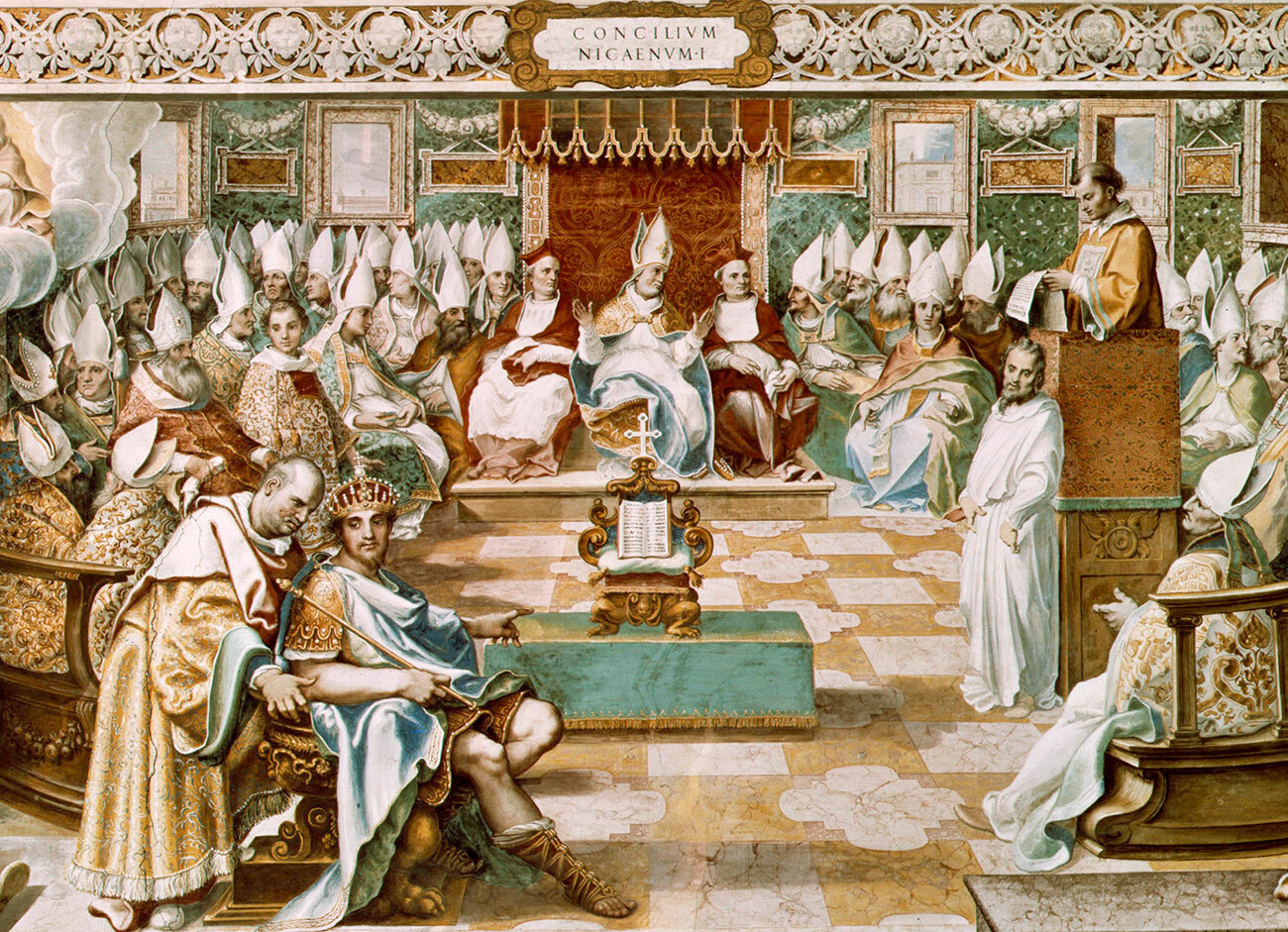

A fresco depicting the First Council of Nicaea at the Vatican's Sixtine Salon

Cesare NebbiaHow was it even possible for the Christian Church to split into a Western one and an Eastern one? Well, the political division of the Roman Empire facilitated the religious division. In the early 4th century, Emperor Constantine ended the persecution of Christians and allowed them to officially practice their faith. He also called and presided over the first ecumenical council, where the Christian creed was accepted, according to which God the Son and God the Father were of one substance; and other important Christian canons were also codified and promulgated.

In an attempt to flee from the barbarous tribes that threatened and attacked Rome, Constantine also moved the empire’s capital to Constantinople. In their struggle for power, the descendants of Constantine practically split the unified empire into the Western one (with Rome as its center) and the Eastern one (with its center in Constantinople).

Then, Byzantium appointed its own bishop, though nominally still subordinate to the Pope. In the 5th century, however, the Byzantine bishop assumed the title of Ecumenical Patriarch. He still recognized the Pope’s primacy, but considered himself independent.

Thoughtful Cardinal, 1904

Jose FrappaThe Pope considered himself the rightful hierarch of the entire Christian Church. This was first and foremost based on Rome’s status as the former empire’s capital, and second, on the claim that he was the direct heir of the first Pope – the apostle Peter. Rome perceived its leadership not as a patriarch – “the first among equals” – but rather it wanted to be the only central controlling body.

However, not only Byzantium but also the other Churches of the East – Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria – fundamentally disagreed with this. They recognized the Byzantine Ecumenical Patriarch, but they refused to recognize the Pope as the sole ruler of the entire Church. For example, according to legend the Church of Alexandria was founded by Saint Mark, and its influence extended to the whole of Egypt. Also, the head of the Church held both the titles of the Pope and the Patriarch (and often served as a mediator in disputes between Rome and Constantinople).

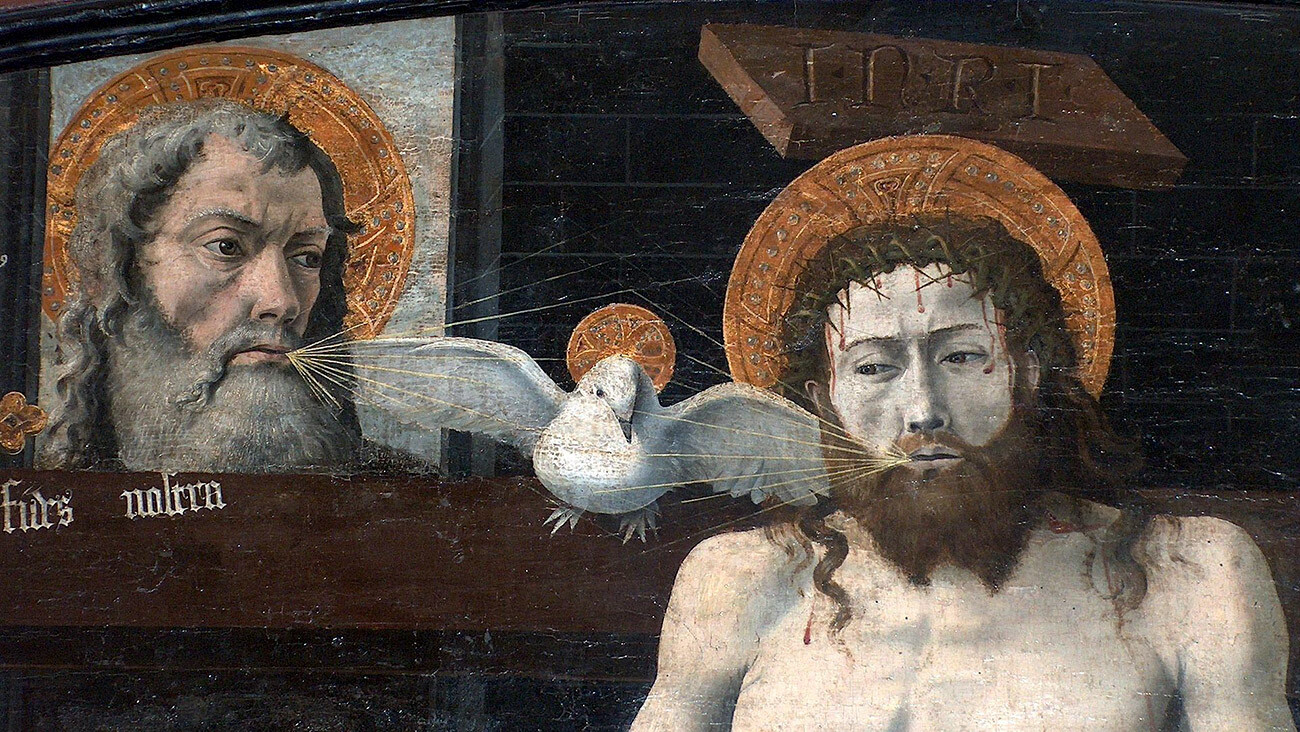

The doctrine of the Filioque, from the the high altar of the chapelle Saint-Marcellin, Boulbon, France (fragment)

Public domainOne of the first and main theological disputes was associated with the Holy Trinity. Saint Augustine, a theologian and the bishop of North Africa, developed the doctrine of filioque which claimed that God the Father and God the Son were both original points of the Holy Spirit. The Latin Western Church accepted this doctrine, whereas the Eastern Church rejected it because according to a more ancient tradition in the Bible, only God the Father is the origin point of the Holy Spirit, as well as of God the Son.

Eastern hierarchs saw in this a distortion of the New Testament and the diminishing role of the Holy Spirit. Hence, Orthodox Christianity considered itself the true doctrine (“orthodox” translates as “correct” doctrine).

The acceptance of filioque by Rome into the official Christian creed at the beginning of the 11th century is considered one of the main reasons for the split.

Aside from that, many liturgical disputes arose between East and West, for example, what bread should be used in the most important rite – the Eucharist. The Eastern Church advocated the use of leavened bread, while the Western Church embraced the use of unleavened bread. Eastern Christians condemned the use of unleavened bread, seeing in it a return to Judaism. Such “dead bread” only represented the body of Christ, but not his soul.

Pope Leo IX receives a message from the Emperor (Relic of the Holy Blood of Jesus from Weingarten Abbey)

Landesmuseum WürttembergEssentially, the Christian Church never was truly unified (perhaps only in the very beginning). Despite all ecumenical councils and attempts to unify the Church, the disputes and confrontations between the bishops of Rome and Byzantium couldn’t be quenched. While the East professed the dogmas accepted during the ecumenical council, Rome was affected by many new influences from invading tribes – the Germans, the Franks and so on. For example, the Normans conquered a part of Southern Italy, which was within the sphere of influence of Constantinople. The Greek Church rites were replaced by Latin ones.

In response, Byzantine Patriarch Michael I Cerularius closed the “Latin” churches in Constantinople; moreover, the executors of the Patriarch’s will began to destroy Latin unleavened bread for their rites. Cerularius also wanted the Pope to recognize the Patriarch as his equal. In 1054, Pope Leo IX refused and sent his messengers to Constantinople to settle the matter. He also sent with them a counterfeit document claiming that allegedly Emperor Constantine himself granted the Pope unlimited power over the entire Christian Church. The situation was further complicated by the fact that the Pope also counted on the Byzantine Empire’s military aid in the struggle against the Normans.

The Patriarch discovered the forgery and refused the Pope, after which the Pope’s messengers excommunicated the Patriarch, in response to which the Patriarch excommunicated them and the Pope.

Baptism of Olga in Constantinople

Ivan AkimovSaint Olga is considered the first ruler of Old Rus’ to accept Christianity. In 988, her grandson, Prince Vladimir, converted all of Rus’ to Christianity, making it the official religion. The chronicles describe in detail how he went about choosing his faith, that envoys from different religions came and tried to persuade him to accept God. The Pope’s messengers came, as well as the “Greek philosophers” from Constantinople. Allegedly, the liturgical rituals of the Eastern Christian Church were more to Vladimir’s liking.

Most likely Vladimir didn’t want to fall under the sole influence of the Pope. Besides, Rus’ and Byzantium had substantial trade and political ties. Thus, conversion to Byzantine’s Christianity brought more benefits. In 988, Vladimir captured the Byzantine city of Korsun (now Khersones in Crimea) and demanded to marry the emperor’s sister, Anna, in exchange for peace.

The emperor, under the threat of Vladimir sacking Constantinople, agreed, but under one condition – Vladimir had to convert to Christianity. It seems the emperor realized that this way he could “tame” his wild neighbor who already led several attacks on Byzantium. Along with Anna, clerics and church ministers from Constantinople traveled to Rus’ and began converting the Russians to Christianity, spreading literacy and teaching the Divine Law.

By the year of the official split of the two Churches in 1054, Rus’ still didn’t have autocephaly or even its own Slavic bishops; all of them were Greek, sent by Byzantium. Hence, the young Russian Church was still very dependent on Eastern Rome and followed its way of “Orthodoxy.”

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox