The Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) criminals, who imposed the reign of fear on the city’s residents in the late 1920s couldn’t have imagined that the wretched homeless woman huddled in the corner of a flophouse was a sign that the game would soon be up. Pretending to be a rough sleeper, legendary police department chief Paulina Onushonok infiltrated criminal haunts and ended a long crime spree in Ligovka, the former capital’s most dangerous district.

A flophouse

Semen Fridlyand/MAMM/MDFThe bandits who operated in Leningrad in the 1920s had no scruples about murdering both city residents and law-enforcers. For example, the brutal killing of criminal investigation officer Aleksandr Skalberg by a gang led by Ivan Belov, nicknamed ‘Vanka-Belka’, caused a real public outcry. It was alleged that one of Belov’s accomplices let himself be recruited by Skalberg, but then lured him into a trap. Four of Belov’s thugs tortured the law-enforcer for a long time and then gruesomely murdered him.

After the murder, a war broke out between the police and the gang members: During the fall of 1920 and in early 1921, five police officers and four bandits were killed in skirmishes and, by the spring of 1921, Belov’s gang had murdered 27 and wounded 18 people, while committing over 200 thefts, robberies and violent hold-ups, journalist Andrei Konstantinov notes in his book ‘Gangland Petersburg’.

Leningrad in the 1920s

Public domainThe resourcefulness of the gangland kingpins damaged the credibility of the law-enforcement authorities. Thus, the city residents simply didn’t believe in the liquidation of criminal “godfather” Lyonka Panteleyev - a former police officer who robbed and murdered residents of Petrograd (later Leningrad and now St. Petersburg) for more than a year - and the authorities had to put his corpse on public display to prove it. In particular, Panteleyev had become “celebrated” not only for his violent robberies, but also for the murder of the chief of the 3rd police department and a daring escape from prison, with the help of an accomplice infiltrated into the law-enforcement bodies.

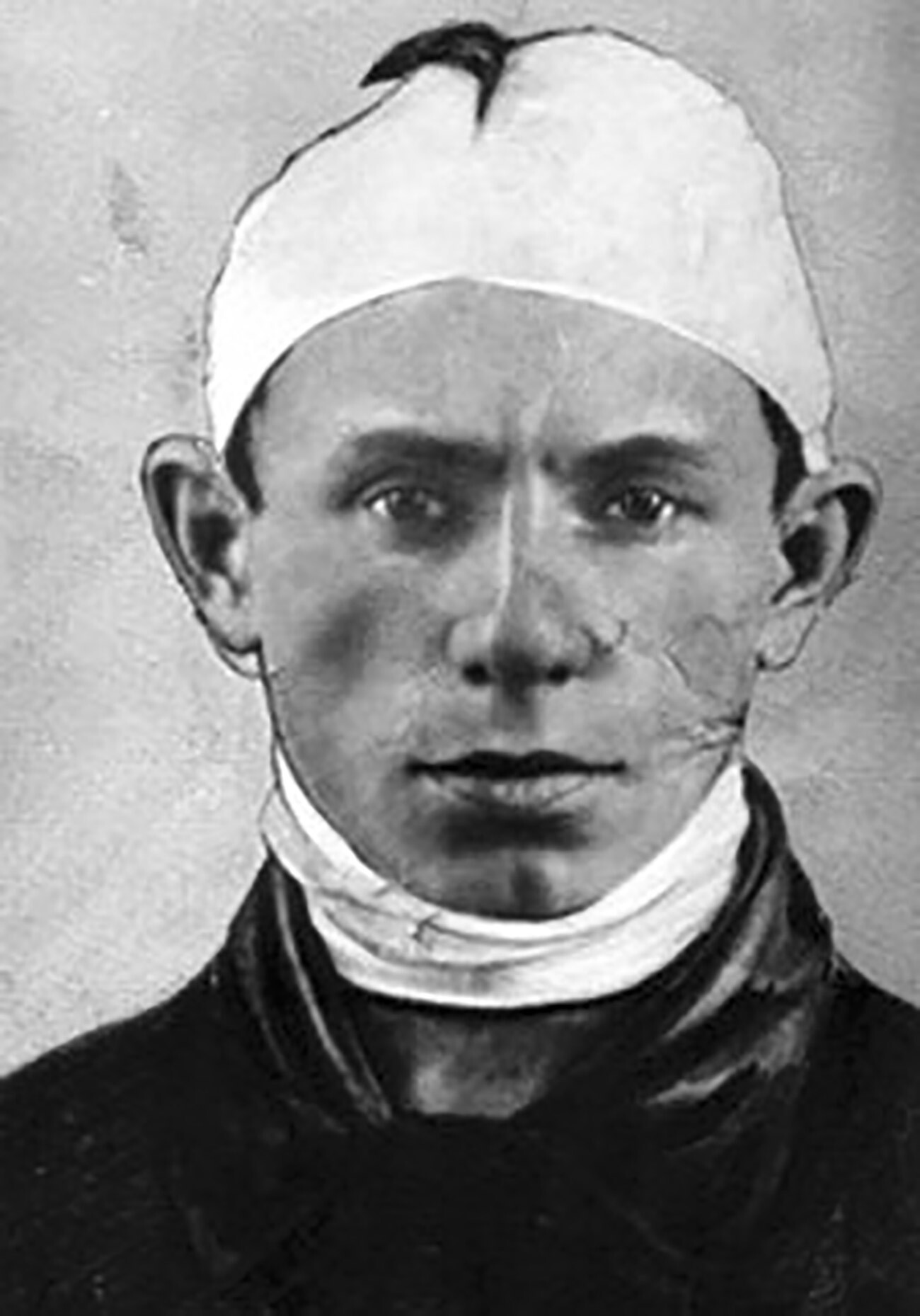

Lyonka Panteleyev

Public domainCriminals of this caliber had many haunts around the whole city; they controlled an extensive underground network and, as a rule, the trail would eventually lead to Ligovka, where both police officers and gang members routinely lost their lives in raids on criminal hideouts.

It was precisely this district that was within the remit of the 11th Leningrad police department, of which Paulina Onushonok was appointed chief. But how did a woman end up in such a senior position in the first place?

Paulina Seglina was born in 1892 in a settlement in the Russian Empire’s Governorate of Livonia (present-day Latvia) to the family of a poor Latvian peasant named Jan Segliņ, who worked for a German baron. In 1905, with the outbreak of the first Russian Revolution, Paulina’s brothers Anton and Karl led a laborers’ revolt: They burnt and robbed estates and distributed the spoils among the peasants. Their 13-year-old sister assisted them as a messenger. Shortly afterwards, the revolt was suppressed, the brothers were killed and the father was kicked off his own land. In 1906, the surviving members of the family moved to Riga. There, Paulina started working at a canning factory and then found a job at a printing press. Soon she joined a Marxist group, whose leader, underground political worker Dmitry Onushonok, became her husband.

Paulina and her husband, Dmitry Onushonok, circa 1928

Archive photoWith the outbreak of World War I (1914-18), the Onushonok family moved to Petrograd. In January 1917, Paulina joined the Bolshevik Party and, in October, took part in the storming of the Winter Palace, the seat of the Provisional Government. In 1918, she started working in the bodies of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage (VChK) and served as an intelligence agent in Riga, writes Alexei Skilyagin in his book ‘Events and People of the Leningrad Police: Outlines of a History’.

Kingisepp Young Pioneer detachment. Paulina Onushonok pictured in center

Kingisepp Historical and Local MuseumIn 1922, Dmitry Onushonok was sent to the city of Kingisepp to guard Soviet Russia’s northwestern border, while his wife became leader of one of the country’s first Young Pioneer detachments. She organized activity clubs and took part in instructing children, immersing them in aspects of the work of the border guards.

In the course of two years, as a result of the successful efforts of policewoman and teacher Paulina Onushonok, the Kingisepp Young Pioneer detachment was transformed into a center, where homeless children and juvenile delinquents from the whole of the Leningrad Province began to be sent for re-education.

Onushonok as a head of Leningrad's Kingisepp District police department, 1928

Archive photoIn 1928, Onushonok became head of the Kingisepp District police department: It was the first time that a woman had been appointed to such a senior position in the USSR. Within a year, the police unit she had been entrusted with was declared the best in Leningrad Region - and this was despite the fact that it was located in a frontier zone where smugglers and saboteurs operated. In recognition of her services, Paulina Onushonok was again promoted - to chief of the 11th Leningrad police department.

Ligovka was one of Leningrad's most dangerous districts in the 1920s

Archive photoPaulina Onushonok’s geographical remit included the railway station, the flea market where stolen goods were off-loaded and the numerous flophouses, where the city’s most hardened gangsters were based. To tackle them, the police department chief picked a tactic that was widespread at the time, but which was also extremely perilous - she went undercover. At night, she would go out dressed as a homeless person, infiltrate criminal haunts and collect information about malefactors. During the day, she would plan where and how to mount raids on them. In addition, during the night and in the evening, her men would carry out enhanced patrols of the area.

A police detachment formed from female workers in Petrograd

MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIn parallel, she initiated the setting up of hostels for homeless people, including homeless children, and a system of finding work for them in order to eliminate the causes of crimes of necessity. It was also at the behest of Onushonok, with her experience of working with troubled young people, that the country’s first juvenile delinquent rooms were opened at the 11th police department. There, homeless children were kept under supervision and re-educated, in the hope of them not growing up to be criminals.

Homeless children with escorts on the street

K.Kuznetsov/MAMM/MDFHer police department soon became the top police unit in the campaign to clean up Leningrad. “In a short space of time, the riotous and noisy district of Ligovka has become a well-appointed workers’ boulevard and this is to your enormous credit.” So wrote the grateful women workers of a spinning-and-weaving factory located in Ligovka to Onushonok. And, in 1933, Paulina Onushonok became one of the country’s first female recipients of the prestigious Order of the Labor Red Banner.

Paulina Onushonok in 1937

Archive photoInterestingly, Paulina and Dmitry Onushonok had no offspring of their own - but they did raise six adopted children.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox