When, in the fall of 1944, GRU operative Igor Guzenko, stationed at the time at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, was told he was being recalled to Moscow, the news did not sit well with him. The operative was by then used to a comfortable Western lifestyle and did not at all wish to return to the USSR, which was still dealing with the catastrophic aftermath of World War II. However, the only thing he could accomplish was to postpone his departure.

On September 6, 1945, Guzenko went to the immigration bureau in Canada with a request to grant him citizenship. Word quickly reached Prime-Minister WL Mackenzie King, as well as the Soviet embassy, which ended up discovering that a number of secret code books and sensitive decoding materials had gone missing. Four Soviet agents were sent to his apartment on the night he was found out, but Guzenko and his family spent it at their neighbors’ house. The following day, the family was placed under protection by the Canadian police.

Thanks to Guzenko’s testimony and the documents he passed along to the Canadian authorities, several dozen people ended up being charged with spying for the USSR - among them, a Canadian member of Parliament.

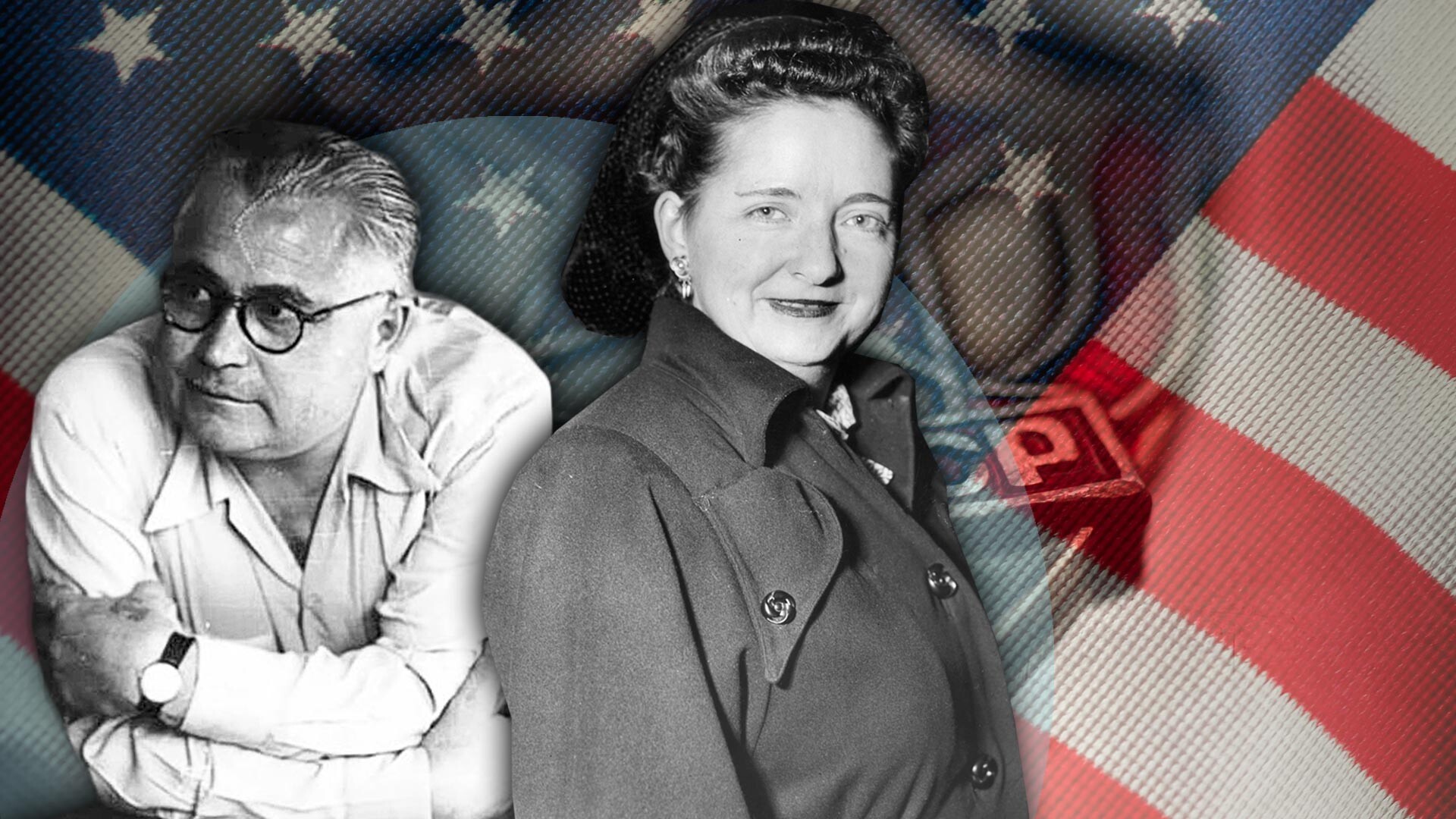

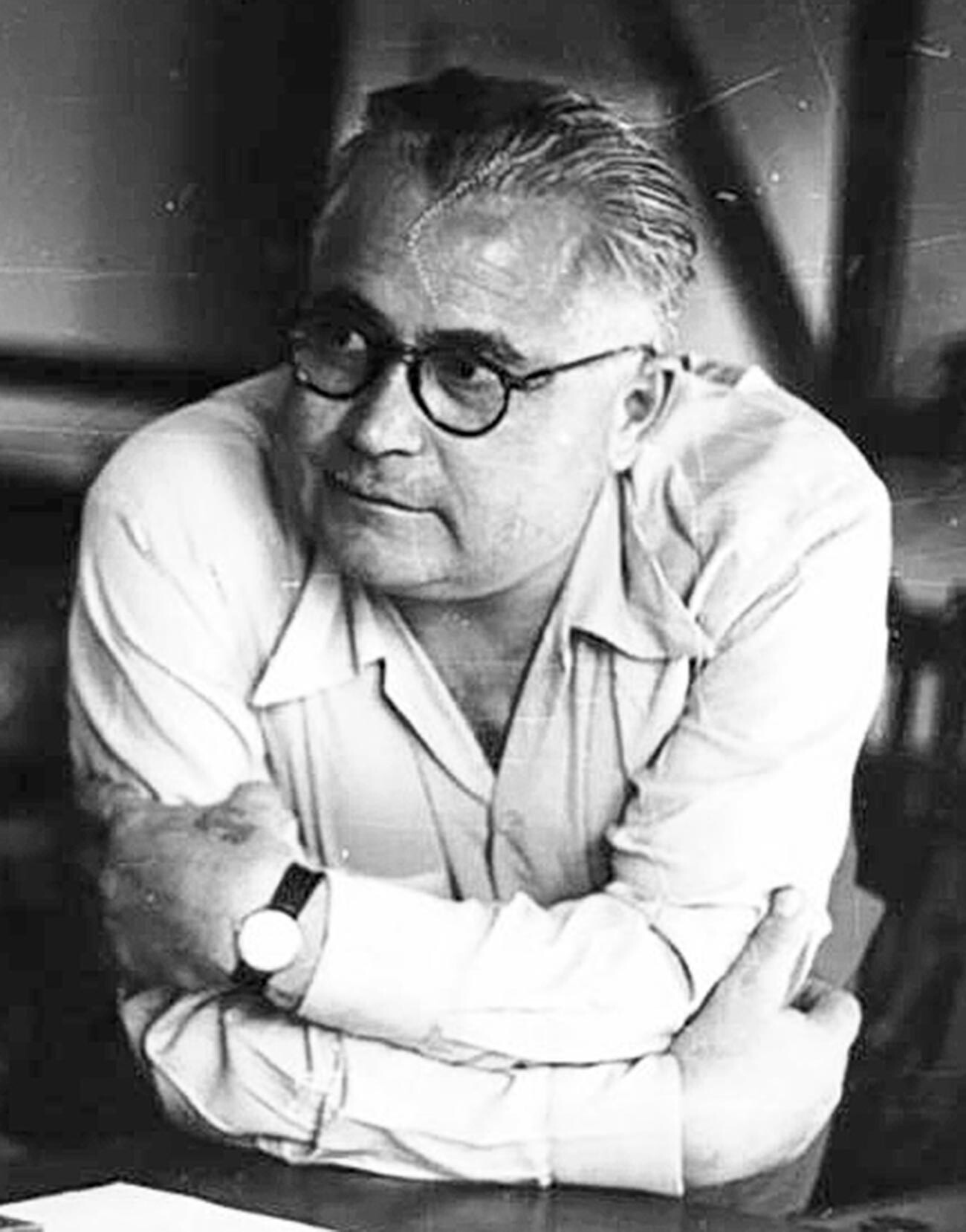

This young communist, known in Moscow by the nickname ‘Umnitsa’ (“Smart girl”), practically managed to collapse the entire Soviet spy network in the United States in 1945. She had spent the 1930s acquiring valuable intelligence for the USSR while working at the Mussolini-curated Italian Library of Information in New York, which she followed with a position as chief assistant to influential Soviet operative Jacob Golos - as well as being his lover.

After Golos’s sudden death in 1943, Bentley’s desire to work for the USSR noticeably waned. She was prone to psychological instability and constant doubts about the righteousness of her work, as well as having a drinking problem. Two years later, ‘Umnitsa’ went to the FBI with a large list containing the names of Soviet agents operating in North America.

The Petrovs - Vladimir and Yevdokia - held minor posts at the Soviet embassy in Canberra. They were also intelligence personnel. In 1953, Soviet security chief Marshal Lavrentiy Beria lost in the power struggle following Joseph Stalin’s death and was arrested and executed by firing squad. Vladimir began to worry that the wave of repressions against personnel that served under the former security chief would soon reach Australia.

On April 3, 1954, Petrov asked the Australians for political asylum - unbeknownst to his wife, who was in another city in Australia at the time. Having found out, Moscow immediately ordered to detain and send back at least her. Two Soviet agents forcefully dragged Yevdokia and stuck her on a special flight bound for Russia. On the personal orders of Australian prime-minister Robert Menzies, the police intercepted the flight while it was refueling in Darwin. The spouses spent the remainder of their days living on the outskirts of Melbourne, under the protection of Australian counter-intelligence agencies.

For 20 years, GRU major general Dmitry Polyakov had been a loyal and committed servant of American intelligence. The likely reason for this can be seen in the tragic story of his son: a large sum was required for the treatment of the severely ill child, which led to Polyakov addressing his superiors. For reasons that remain unknown, his request was denied and his boy died.

This resulted in Polyakov contacting the FBI during a work visit to the United States in 1961. In the years that followed, he would disclose the identities of some 1,500 Soviet agents to the Americans. Even though he had been receiving repeated requests by his handlers to leave the Soviet Union for good, his answer remained the same: “Don’t wait for me. I will never come to the U.S. I’m not doing this for you. I’m doing this for my country. I was born a Russian and I’ll die a Russian.”

Polyakov was outed in 1986 after retirement, due to health reasons. He was executed for treason two years later.

In June, 1978, Vladimir Rezun, who was a GRU resident agent in Geneva, escaped to the UK with the help of British intelligence services, together with his wife and two children. Back home in the USSR, the defector was declared a traitor and sentenced to death in absentia.

Rezun decided to dedicate his days in exile to reenvisioning World War II history. A whole host of books authored by the former spy under the pen name ‘Viktor Suvorov’ propose and vehemently defend the hypothesis that the Soviet Union was planning to carry out a preventive strike on Nazi Germany, while the Red Army was readying itself not for defense, but for an offensive “freedom mission” in Europe. Suvorov’s work sustained repeated criticism from the academic community, allegedly, for its numerous errors and inaccuracies, causing the theory to be invalidated.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox