Who are the two bronze guys on Red Square standing for Russian freedom?

This monument survived even the reconstruction of Moscow in the 1930s, when many Tsarist-era monuments and buildings were demolished. The reason for its survival owes to the patriotic meaning of the memorial, symbolizing the unity between the folk (Minin, a common leader), and state power (Pozharsky, a prince and high-ranking military official). This unity is what helped save Moscow from foreign invaders.

In Russia’s darkest times, such as the Tatar yoke, Polish invasion, Napoleonic War and the Great Patriotic War (World War II), a similar pattern played out. Even though it seemed that the end was near, and that nothing could save Russia from occupation and destruction, the common people united under the leadership of state leaders and fought the enemy until victory was accomplished. This is the feat that Minin and Pozharsky accomplished, and here’s the true story.

The Polish invasion and occupation

Red Square in Moscow, Russia, circa 1870.

Henry Guttmann/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThe early 17th century is known as “Time of Troubles” in Russian history because the country suffered a dynastic succession crisis, as well as peasant uprisings. An impostor known as False Dmitry II, calling himself Ivan the Terrible’s son, was near Moscow with his forces, and former Tsar Vasily Shuyskiy had been deposed from the throne.

In 1610, the government was controlled by the ‘Seven Boyars,’ and they decided to surrender the city to the Polish army. That country’s military leaders wanted to make prince Vladislav king of Russia, but in 1611 the Polish forces were blocked inside the Kremlin and began to starve. The time had come to eject the invaders from the Russian capital, and that’s when Minin and Pozharsky entered the historical limelight.

Kuzma Minin

"Appeal of Minin", 1896. Konstantin Makovsky

Konstantin MakovskyWhile his origins are mysterious - we don’t even know his father’s name – some experts believe that Minin was of Tatar descent. We do know for sure that Kuzma was a citizen of Nizhny Novgorod, and that he worked as a butcher and enjoyed certain social prestige. A natural born leader, Minin often appeared at public gatherings, and he persuaded people to form a national militia to kick the Poles out of the Kremlin and restore Russian power.

Using his connections, Minin assessed the property of Nizhny Novgorod’s citizens and made them pay one third of their savings to support the national militia. The property of those who refused to pay was confiscated. This compulsory crowd-funding helped form the core of the national militia, made of professional soldiers who were able to defeat the Polish troops holding out in the Kremlin - one of Europe’s most formidable fortresses.

Dmitry Pozharsky

Russia, Suzdal, Monastery of St Ephimious. Bronze relief depicting Pozharsky and Minin on the door of the small chapel which houses the tomb of Pozharsky

Getty ImagesDescendant from a princely line, Dmitry Pozharsky enjoyed the high rank of the Tsar’s stolnik. Unlike most prominent officials, Pozharsky was renowned for his high moral principles. Devoid of vanity and greed, modest in public and true to his Motherland, Pozharsky was at the same time gentle and introspective.

Serving under Vasiliy Shuyskiy, he fought the Polish invaders, and when the ‘Seven Boyars’ wanted to put Vladislav on the throne, he strongly opposed that treacherous move. In early 1611, Pozharsky fought with the national militia against the Poles, and helped besiege the invaders inside the Kremlin; but he was wounded and taken to his estate in the Nizhny Novgorod region.

The second national militia

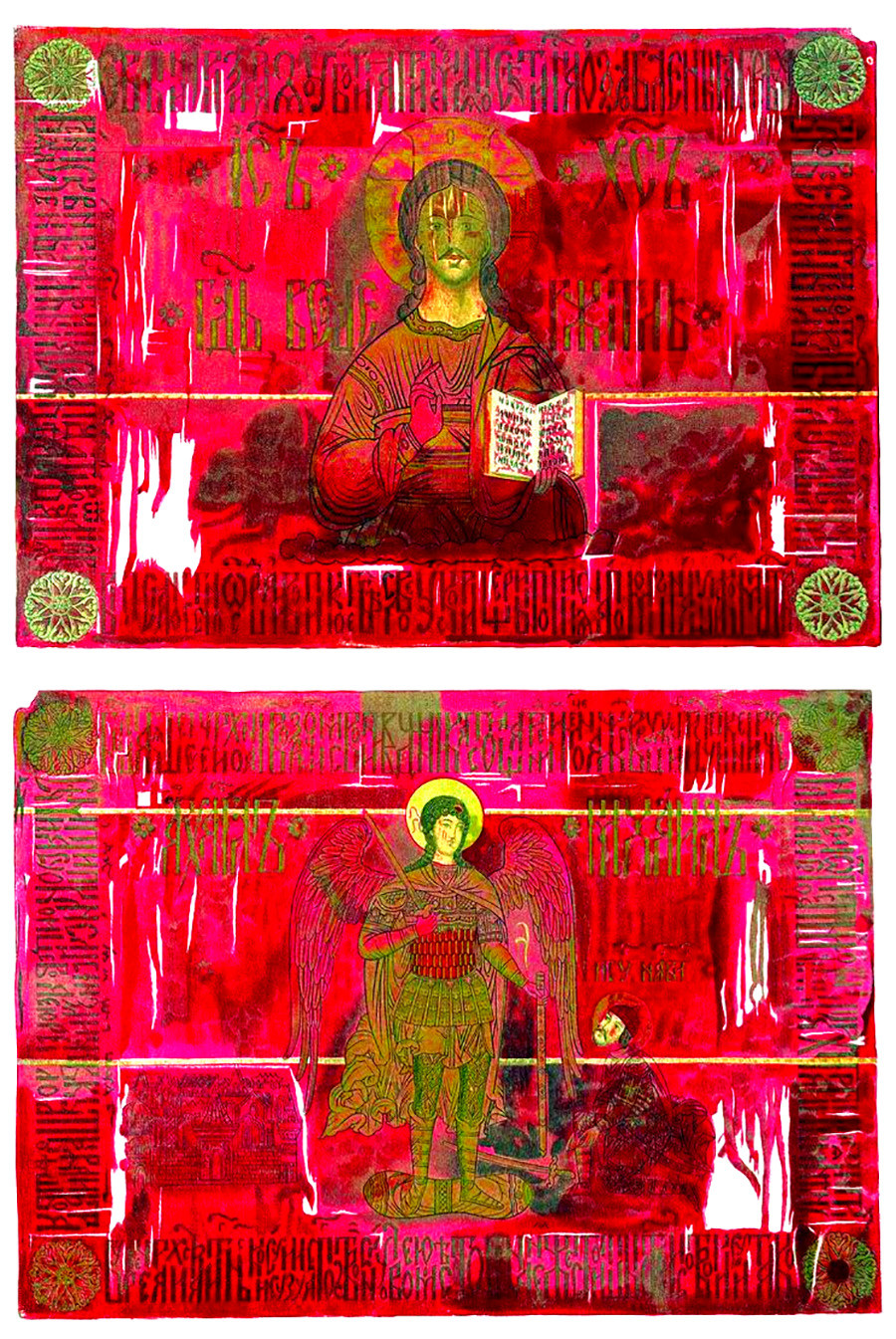

Dmitry Pozharsky's standard. Preserved in the Kremlin Armory.

After Pozharsky’s recovery, the members of the second national militia chose him as their leader. He agreed only on the condition that Minin supervise all finances and equipment of the folk army. Minin and Pozharsky sent letters to many major towns, summoning troops from all the Muscovite lands. In March, the national militia went to Yaroslavl, where it gathered more troops, and they even persuaded the Swedish and German governments to send troops to help defeat the Poles.

In early September 1612, the national militia reached Moscow. After three days of fighting, the Polish forces were battered. After two months, the besieged Poles were on the brink of cannibalism. On Nov. 5, 1612, the enemy forces were evicted from the Kremlin, which is why Nov. 4 is commemorated as National Unity Day - in memory of the national army that defeated the invaders and preserved Russian sovereignty.

Ernst Lissner, The Expulsion of Polish Invaders from the Moscow Kremlin.

Ernst LissnerKuzma Minin and Dmitry Pozharsky continued to serve Russia after the Time of Troubles had ended. They both were given prominent positions in the Tsar’s court, which they held until the end of their days.

The monument

The monument to Minin and Pozharsky on its former place in front of GUM

SputnikThis month the monument to Minin and Pozharsky, which is located on Red Square, marks its 200th anniversary. Plans for the monument were hatched in 1803, and in 1808 Emperor Alexander I endorsed the idea, and issued a decree that started a national fundraising campaign for the monument. The Russian-Napoleonic War of 1812 only intensified the patriotic sentiment behind this idea.

The monument was cast in 1816, made of 1,100 tons of copper. This was the world’s first monument of such a large size that was cast in a single process, which lasted 10 hours. On Feb. 20, 1818, the monument was opened to the public, in the center of Red Square in front of the main entrance to the Upper Trading Rows, now known as GUM.

Later in 1931, the monument was moved to its current place in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral in order to free up space for Soviet military parades. Today, the monument is an inherent part of the iconic view of Red Square. "To Citizen Minin and Prince Pozharsky, The Grateful Russia, year 1818," the inscription reads.

The monument to Minin and Pozharsky (contemporary view)

Getty ImagesIf you want to know more about the early years of the Romanovs, read about the first Romanov, Tsar Mikhail, or visit The Trinity-Ipatiev Monastery where he was in hiding during the Time of Troubles. And for something different, can you guess what these words in Russian cursive mean?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox