The foreign charlatans who failed to make it big in Russia

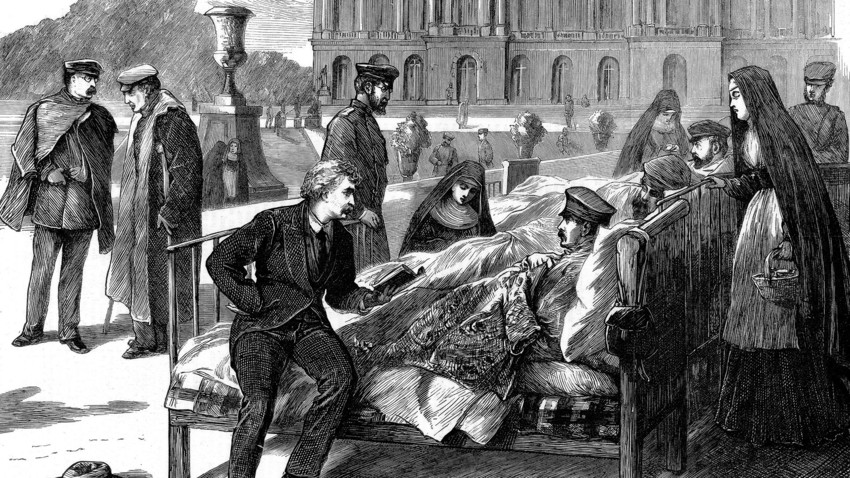

Daniel Home reading to wounded German officers in the military hospital at Versailles. Franco-Prussian War, 1870. From The Graphic. (London, 26 November 1870).

Getty Images1. Roman Maddox (Medoks): the conman who infuriated two Russian emperors

An intelligent man with refined manners, the charismatic Roman Maddox (Medoks) had the guts to disguise himself as a high-ranking military officer, as well as a man steeped in the mysteries of Russian secret societies. With a gift for persuasion, he tricked many people into trusting and believing him, and he incensed two Russian emperors with his escapades.

Maddox was born in Russia to a German mother and an English father, Michael Maddox, who was co-founder of the Petrovsky Theater, the first permanent opera house in Moscow and predecessor to the Bolshoi Theater.

Maddox Jr., however, was not such a productive and fine citizen. In fact, he was shunned by his family due to his “immoral way of life.” Spoiled and raised with a lavish lifestyle, the young Maddox didn’t want to work, and sought to enrich himself through dishonest activities.

In 1812, Maddox acquired the uniform of an imperial guards officer: During this time of war with Napoleon anyone serving in the Tsar’s personal regiments was trusted and feared. Maddox forged papers claiming that he had been sent by the War Ministry to the Caucasus region in order to gather volunteers for the fight against the French.

Without properly checking the officer’s identity, Caucasus region authorities loaned him the fantastic sum of 10,000 rubles to gather his militia. In February 1813, however, his ruse was uncovered, and Maddox was arrested and sent to St. Petersburg.

Emperor Alexander I was furious, and Maddox was jailed in the Petropavlovskaya Fortress, where he spent 14 years. In 1827, shortly after ascending the throne, Emperor Nicholas I commuted his sentence to exile in Irkutsk, Siberia where many were serving sentences for participating in the Decembrist revolt of 1825.

Aware of how much Nicholas hated the Decembrists, one day Maddox just happened to “discover” a new secret society among the rebels, and informed the Tsar. When an investigation started, Maddox presented ‘evidence,’ including a membership card for the new secret society. Maddox was quickly brought to St. Petersburg at the emperor’s personal order. While the investigation was under way, Maddox lived the high life in Moscow and St. Petersburg, courting women, going to theaters and bragging of his heroism.

The investigation soon revealed, however, that the “secret society” was entirely fabricated by Maddox, including the membership card that he had made himself. After a few months, the emperor learned that he’d been fooled and was outraged, just like his older brother, Alexander, years before. This time, Maddox was sentenced to 22 years in the infamous Shlisselburg prison. He served his entire sentence, but died shortly after release in 1856.

2. Cagliostro: ridiculed in Catherine the Great’s play

Count Cagliostro. Engraving. Paris, Bibliothèque Polonaise De Paris Societé Historique Et Litteraire Polonaise

Getty ImagesBefore coming to Russia, Giuseppe Balsamo, widely known as “Count Cagliostro,” was already notorious in Europe. He lived the chic life of a famous court magician, psychic healer and alchemist. After spending a few years in London, he set out for Russia, hoping to find more rich and powerful fools there.

Cagliostro was known for his coarse manners, and he wrote and spoke with vulgar mistakes, but as a contemporary in Russia recalls, Cagliostro “had the wonderful ability to hold listeners’ attention for hours with his speeches, full of philosophical and mystical maxims, and seemingly abstruse metaphors.”

In 1779, Cagliostro arrived in St. Petersburg, and he introduced himself as a doctor. Hoping to make a name for himself, he accepted all patients, from the poorest to the noblest. Cagliostro also conducted spirit seances and promised to multiply people’s gold items. He even played this trick on the powerful Count Potyomkin, Catherine the Great’s favorite and the most important state official of the time. Potyomkin also had an affair with Cagliostro’s wife, Lorenza Seraphina.

Cagliostro’s ‘magic’ act crumbled when he promised to heal the newborn son of the wealthy and influential Prince Gagarin - the baby was near death. Cagliostro took the baby home for two weeks, and then a healthy baby was returned to the happy mother. The problem, however, was that it was another baby! Princess Gagarina reported this crass fraud to her friends, and eventually news of it reached the Empress.

At the same time, court doctors condemned Cagliostro for witchcraft and compromising the medical profession. Also, upon learning of Potyomkin’s romance with Cagliostro’s wife, Catherine became very jealous. The Italian was hastily deported from Russia. About five years later, Catherine made Cagliostro the central figure in “The Deceiver,” a comedy staged in theaters that became popular and successful.

3. Daniel Home: the levitating fraudster

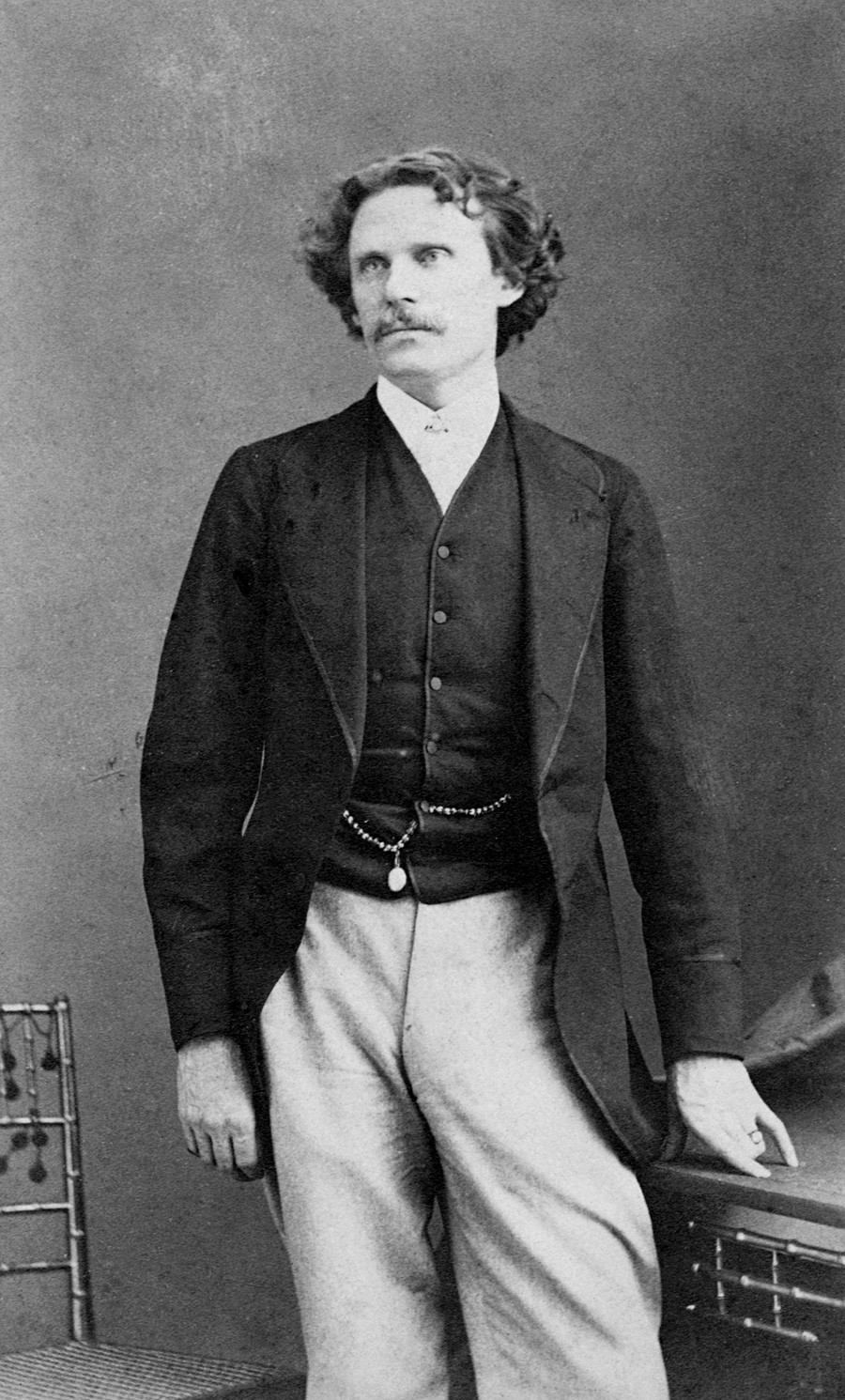

Daniel Dunglas Home.

Getty ImagesDaniel Home, an American of Scottish origin, conducted spirit seances and poltergeist shows since he was 18, but his most famed act was levitation. While investigated numerous times by American doctors and scientists, he was nevertheless declared “not fraudulent.” In 1855, Home came to Europe to do his tricks for Napoleon III and Queen Sophia of The Netherlands, who recalled seeing golden bells soar in the air and knots tying themselves on her handkerchief.

In July 1858 in St. Petersburg, Home conducted a seance in the presence of Emperor Alexander II and his court. The table flew, “spirits” rapped noises around the room, and the Emperor was very pleased. These seances were repeated, and later the Emperor and his guests heard spirits rap Russia’s national anthem, “God Save the Tsar.” Like most of Home’s patrons, the Imperial family didn’t pay for seances; instead, the pay came in the form of lavish gifts such as expensive jewelry.

There was something else, besides money, that drew Home to Russia - women. His first marriage to a Russian lady ended with his wife’s untimely death in 1862. Then in 1871, he married another Russian woman, the wealthy Julia Gloumeline. His seances, however, stopped shortly after, and family life was probably not the most important reason.

In 1871, a commission was assembled by St. Petersburg scientists to test Home’s psychic powers. Home, however, couldn’t perform a single one of his experiments before the commission. As he retreated to London, St. Petersburg newspapers denounced him as a fraud. It’s not clear whether his experience in Russia had crushed Home, or whether his new wife’s funds were sufficient to support him financially (so he was able to stop performing), but there are no records of Home’s activity after 1871. He retired from performing because of poor health, and died 15 years later in Paris.

On the contrary, read about 3 foreigners who changed Russian history, or find out about foreign food on the Russian table, or find out why some Russians look Asian.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox