“Even before the advent of hi-tech, I made payments using my mobile phone a couple of times,” Russians say jokingly on the internet. People who were young in the 1990s and early 2000s can appreciate the joke.

Typical gopniks of the early 2000s

Silvymaro (CC BY-SA 4.0)At the time, gopniks instilled fear in respectable citizens, threatening them with violence as they robbed them in dark passageways of their mobile phones, which were still scarce at the time, other valuables or just cash. In the Russian language, such attacks are known as gop-stop.

According to the ‘Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language’ compiled by Russian lexicographer and folklore collector Vladimir Dahl (first published in 1863-1866), gop means “hop, jump or blow”. But, in a small dictionary of criminal slang compiled by Dahl in the 1850s or thereabouts - ‘Jargon of St. Petersburg Conmen, Known as Music or Thieves’ Argot’ - the verb gopat means “to sleep rough on the streets”.

Homeless children

Georgy Soshalsky/MAMM/MDFThis meaning doesn’t contradict the more popular explanation of the origin of the words gop and gopnik. According to this account, it is to do with the abbreviation GOP for Gosudarstvennoye Obshchestvo Prizora (‘State Society for the Provision of Care’) in St. Petersburg. At the end of the 19th century, it was housed in one of the buildings of the once fashionable Znamenskaya Hotel (present-day Oktyabrskaya Hotel) in the very center of the city opposite Moskovsky Railway Station. It was an orphanage for poor children and juvenile delinquents.

Znamenskaya Hotel

Public domainAfter the 1917 Revolution, the building was nationalized, but it retained both its function and abbreviation. Only the name changed: Now it was called Gosudarstvennoye Obshchezhitiye Proletariata (‘State Hostel of the Proletariat’). But, in the 1920s, most of its residents were homeless children, rather than workers. Civil War in Russia, epidemics and several years of terrible famine led to a situation whereby there were plenty of homeless children. And it was the residents of this hostel for the homeless who started calling themselves GOPniks. Not engaged in producing anything, they made a living from petty theft, hooliganism and robbery and maintained the bad name of the Ligovka area in St. Petersburg, where their hostel was located.

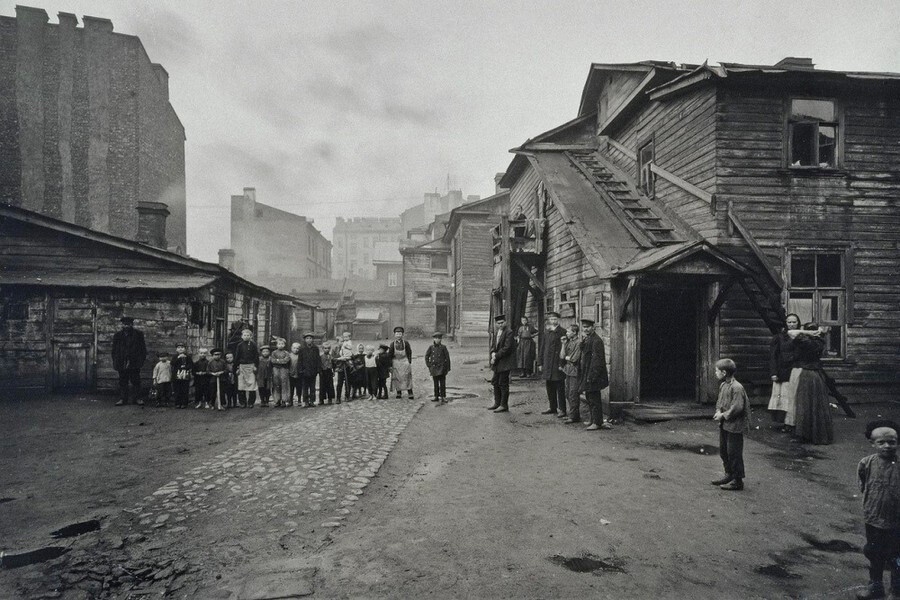

Ligovka area

Public domainAt the time, Ligovka was regarded as the most dangerous and seedy area in Leningrad. It often featured in criminal reports as the scene of crimes that shocked the entire country, be it group rapes or brutal attacks on police inspectors. It was Paulina Onushonok - the first woman to head a police department in the USSR - who succeeded in eradicating crime in the Ligovka area.

She also solved the problem of juvenile delinquency and homelessness among children in the city, as well as the country: It is believed that it was at her initiative that juvenile delinquents’ rooms were set up at police stations in 1935. These carried out educational work with underage hooligans.

Tram surfing in Leningrad, 1928

Public domainThus Paulina Onushonok managed to restore the reputation of Ligovka; as for the gopniks, over time they “migrated” from the city center to the outskirts - to the so-called dormitory districts.

Nowadays, fortunately, you are more likely to come across gopniks in jokes, literature and the movies than on the streets.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox