4 reasons why Russians use Cyrillic

Since its birth, the Cyrillic alphabet has had some major surgery to make it the force it is today. Here’s why it holds court in Russia as opposed to a Latin-based alphabet.

1. Cyrillic was created to bring the lands of Rus under the Orthodox umbrella

Cyrillic handwriting, 17th century

Public domainThe early Cyrillic alphabet was brewed up by disciples of Cyril and Methodius to spread the word of the Bible in the Old Slavonic language. It was also created to drive a wedge between the new parish of the East AND the Catholic parish in Europe (Catholic priests used Latin). In some Balkan states, and later in the ninth and 10th centuries in Kievan Rus, Cyrillic helped to underline the difference between Orthodoxy and Catholicism.

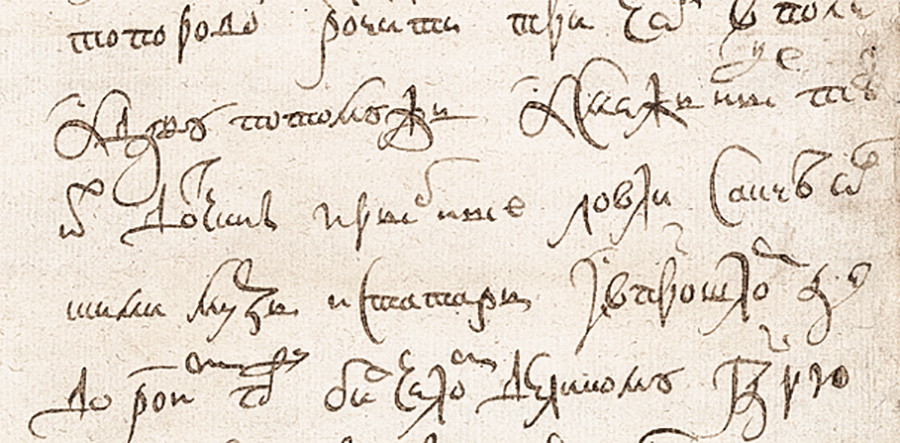

Old Russian writing in a chronicle.

Public domainThe Russian Orthodox Church adopted Old Russian in the 10th century as the official language of services and sermons. As the church was the main educator, Cyrillic became the alphabet for the Old Russian language. It included the full Greek alphabet (24 letters) and has 19 additional letters for Slavonic sounds.

2. Peter the Great simplified Cyrillic to fuel trade with Europe

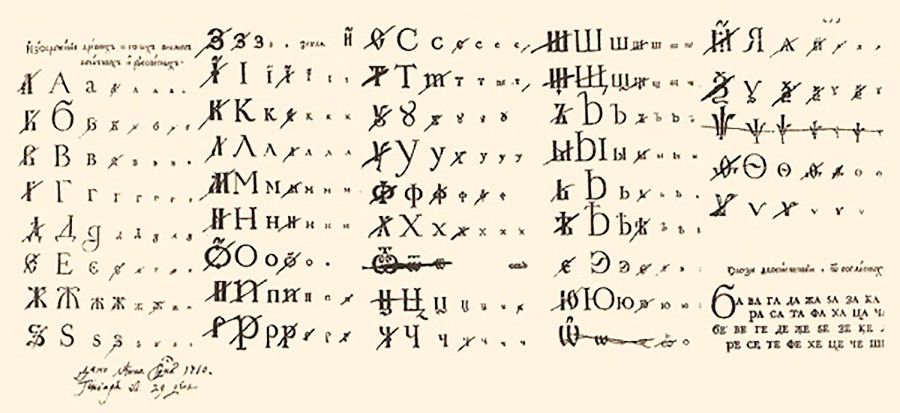

Old Russian alphabet edited by Peter the Great himself.

Public domainPeter the Great introduced the first reform of the Russian language in 1708 and four years later it was fully implemented. The Tsar himself redesigned 32 letters and many of their forms were approximated to Latin ones so they could be easily modeled by type designers in Europe. Peter scrapped many superfluous superscript signs and insisted on capital letters at the start of sentences. Arabic numerals were also introduced instead of the alphabetic numerals used before.

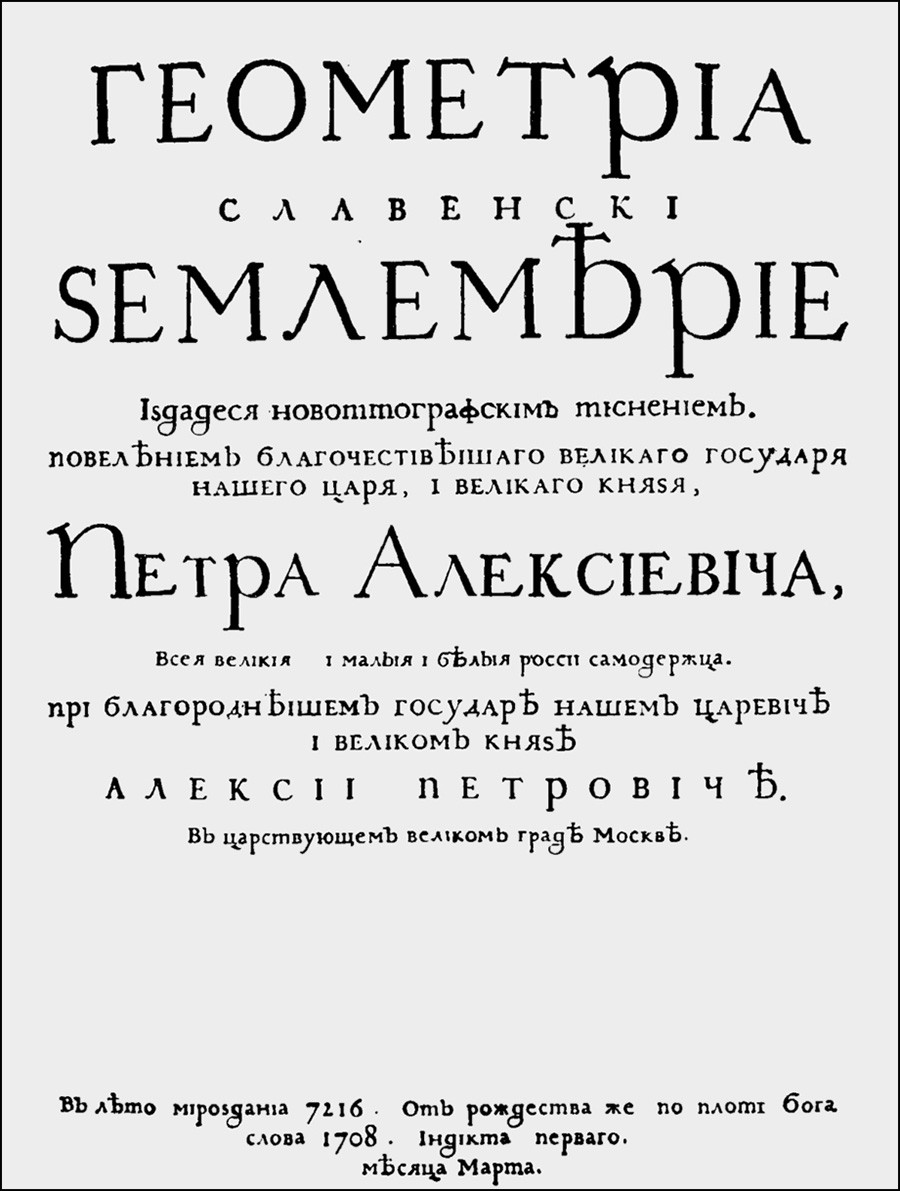

Geometry and Surveying, the first Russian book printed in Peter the Great's civil typeface.

Public domainThe initial metal types cast for the reform’s first font were made in Holland. Along with letters and printing machines, Peter also commissioned the first typesetters and typographers to teach Russians modern methods of book printing. The new typeface was used for books, newspapers, and public adverts.

Peter’s reign built closer business, education, and military ties between Russia and Europe – the Tsar’s civil typeface showcased the Russian language to the world.

3. The Bolshevik’s 1918 Orthographic Reform combatted illiteracy

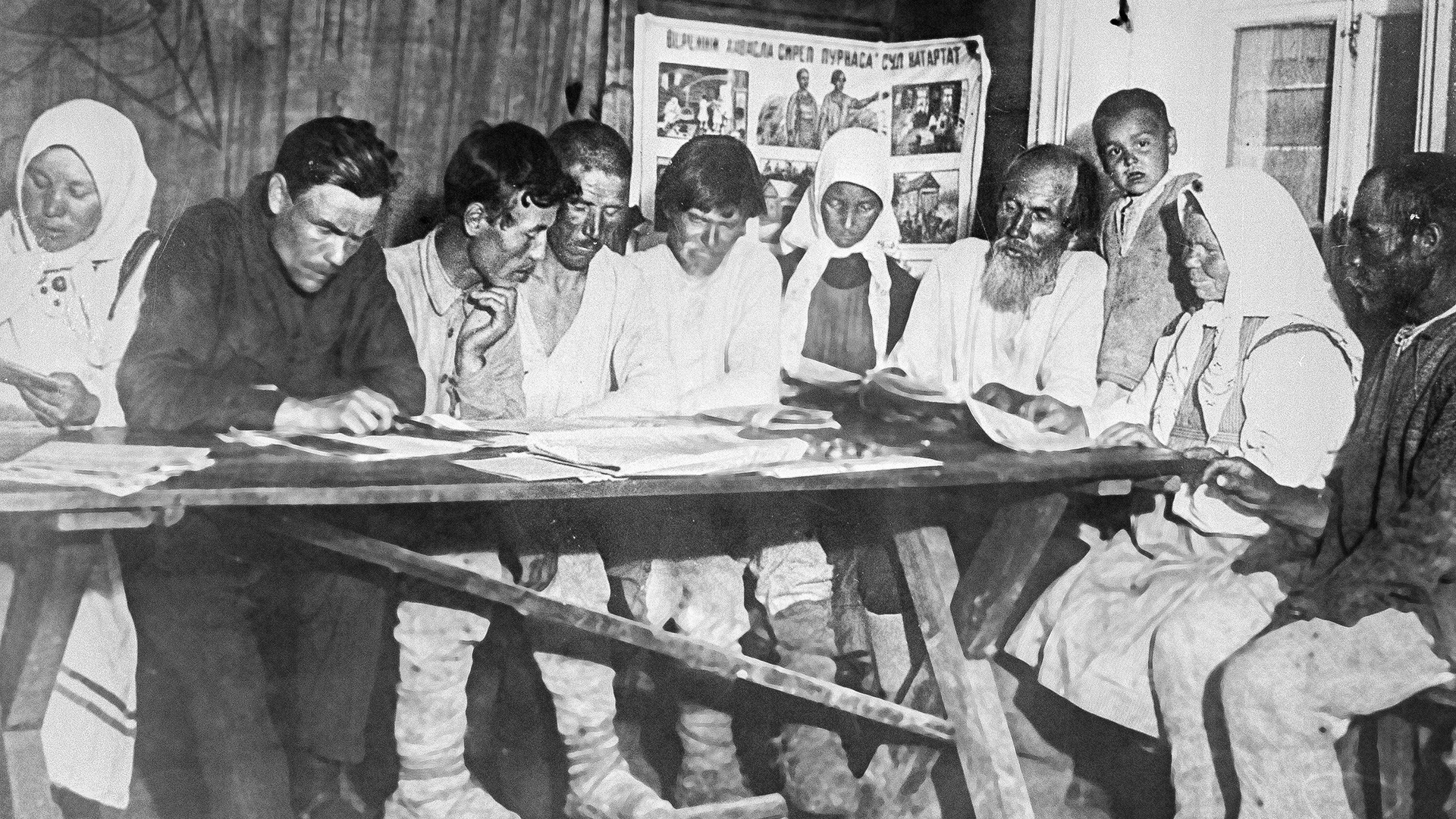

Soviet peasants learning to read and write, 1930s

SputnikThe Russian language and Cyrillic typeface developed through the 18th and 19th centuries and by 1918 included 35 letters. It had complicated rules, even

The reform was rubber-stamped and the Russian alphabet with 33 letters we know today was born. To implement the new linguistic rules Bolshevik officers simply confiscated old letter sets from printing houses. The new version of the Cyrillic alphabet again sent a message to the world: there was a brand new state with a reformed language that would be adopted by millions.

4. Disseminating the Russian language in other communist states

A cartoon showing a book with rules of the Russian language visibly diminish in size. 1956.

Iosif OffengendenIn 1956 the Russian language witnessed its last major reform. Strictly speaking, it didn’t affect the Cyrillic type, it just solved some complicated orthographic cases and made it easier to learn.

The 1955 Warsaw Pact paved the way for Russian to be taught in the countries that signed up. In 1964, 1973, and 1988 further attempts were made to reform the language and resulted in some minor changes. Broadly speaking, we now use the 1956 model of Cyrillic. From the 1990s, Russian typographers started developing Cyrillic fonts for digital and print publishing, while online Cyrillic accounts for six percent of the content found on the top ten million websites, second only to English (54 percent).

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox