In Russia, the deaths of famous people are often surrounded by myths. Thus, according to various legends, Emperor Alexander I didn’t, in fact, die young, but lived to a ripe old age as a recluse in a Siberian monastery; renowned Russian writer Nikolai Gogol was buried alive, because he fell into a lethargic sleep; and the daughter of Nicholas II, Anastasia, survived after the execution of the Imperial family…

Russia's most famou poet Alexander Pushkin himself has not been immune from similar speculation. It is paradoxical that, almost 200 years after his death, new myths about the poet still pop up. For example, a hypothesis has been doing the rounds in the broad reaches of the Russian internet for about 10 years now that Alexander Pushkin didn’t die, but moved to France and continued his writing career under the name of Alexandre Dumas (whose novels in Russia are so popular that they are worn thin by reading and literally every Russian is acquainted with the protagonists of ‘The Three Musketeers’).

Unexpectedly, though, there turn out to be a lot of mysterious coincidences in the biographies of Pushkin and Dumas. Judge for yourself…

In 1836, rumors spread throughout St. Petersburg that Pushkin’s wife, Natalia Goncharova, was having a romantic liaison with the Frenchman Georges-Charles d’Anthès. The impulsive Pushkin couldn’t tolerate such an insult and challenged d’Anthès to a duel, in which the poet was mortally wounded and died two days later. But, he was buried in almost total secrecy.

The death of Russia’s foremost poet was a tragedy and shock for many and St. Petersburgers were inclined to blame the authorities and high society for what had happened. Thousands of people gathered outside the house of the deceased poet to pay their last respects and to express their discontent. To prevent possible unrest, the emperor ordered that a public funeral should not be held. The public was told that the farewell ceremony would take place at St. Isaac’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg, but the coffin, escorted by gendarmes, was taken under cover of night to distant Pskov Province. Pushkin was buried there very quietly, in a monastery not far from his family estate at Mikhailovskoye. Apart from the gendarmes, only one of his friends and a couple of servants were present at the burial.

Such a death and burial offered great scope for flights of fancy and speculation. Furthermore, in the last years of his life, Pushkin often complained of a sense of hopelessness. He was unhappy with his humiliating position at Court and the obligation to attend balls, his difficult relations with Tsar Nicholas I, his huge debts and his wife’s unwillingness to give up their life in the capital and move to the country. There were two possible ways out of this impasse: death or disappearance. On top of that, in his entire life, Pushkin was never allowed to travel abroad and he desperately wanted to see Europe. According to one conspiracy theory, it was the Russian tsar himself who sent Pushkin to Paris as a spy under the name of Alexandre Dumas and allegedly paid off 70,000 rubles of his debts (an enormous amount at the time) for this service.

Alexandre Dumas / Alexander Pushkin

Joseph-Benoît Guichard; Konstantin SomovPushkin was fluent in French and wrote his first literary undertakings in the French language. In other words, he could, hypothetically speaking, have easily written French novels. In addition, all of Dumas’ best-known novels, the ones that brought him literary fame (‘The Three Musketeers’, ‘Twenty Years After’, ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’ and the trilogy about Henry of Navarre), were written after the “death” of Pushkin - in the mid-1840s.

There is another remarkable coincidence. A novel titled ‘The Fencing Master’ was published under Dumas’ name in 1840. The action unfolds in Russia and reveals the author’s acquaintance not only with the names of locations in St. Petersburg, but also the realities of life in Russia of that time.

According to the plot, the author comes into possession of the notes of a fencing master, who taught in Russia. Many of his pupils subsequently became Decembrists - participants in the 1825 revolt by aristocrats in St. Petersburg. The revolt was put down and the Decembrists were exiled to Siberia.

The subject of the Decembrists was painfully close to Pushkin’s heart, as many of them were his friends and he only avoided being one of the conspirators himself, because he was already in exile at the time. He never wrote any prose work in Russian about those events, however.

It is also curious that, in the 1860s, Dumas went on a trip to Russia. After no more than a brief sojourn in the capital, the writer set off for the Caucasus (where Pushkin had also been) and even met the prototypes of some of the characters in ‘The Fencing Master’. Dumas also showed great interest in Russian literature. He translated, among other works, Pushkin’s ‘Ode to Liberty’, whose revolutionary sentiments had led to the Russian poet’s exile, as well as the work of another celebrated Russian poet and writer - Mikhail Lermontov’s verse and his novel, ‘A Hero of Our Time’. It is said that Dumas did not know Russian and was assisted by the writer Dmitry Grigorovich (who was half-French).

Dumas and Pushkin had a remarkable number of things in common. For instance, both had African roots. Pushkin’s great-grandfather was the Ethopian Abram Gannibal, who had been closely associated with Peter the Great, while Dumas’ grandmother was a black slave from the island of Haiti. “He was like a force of nature, because African blood swirled in his veins,” was how Dumas was described by his biographer, André Maurois. Сontemporaries always said similar things about Pushkin.

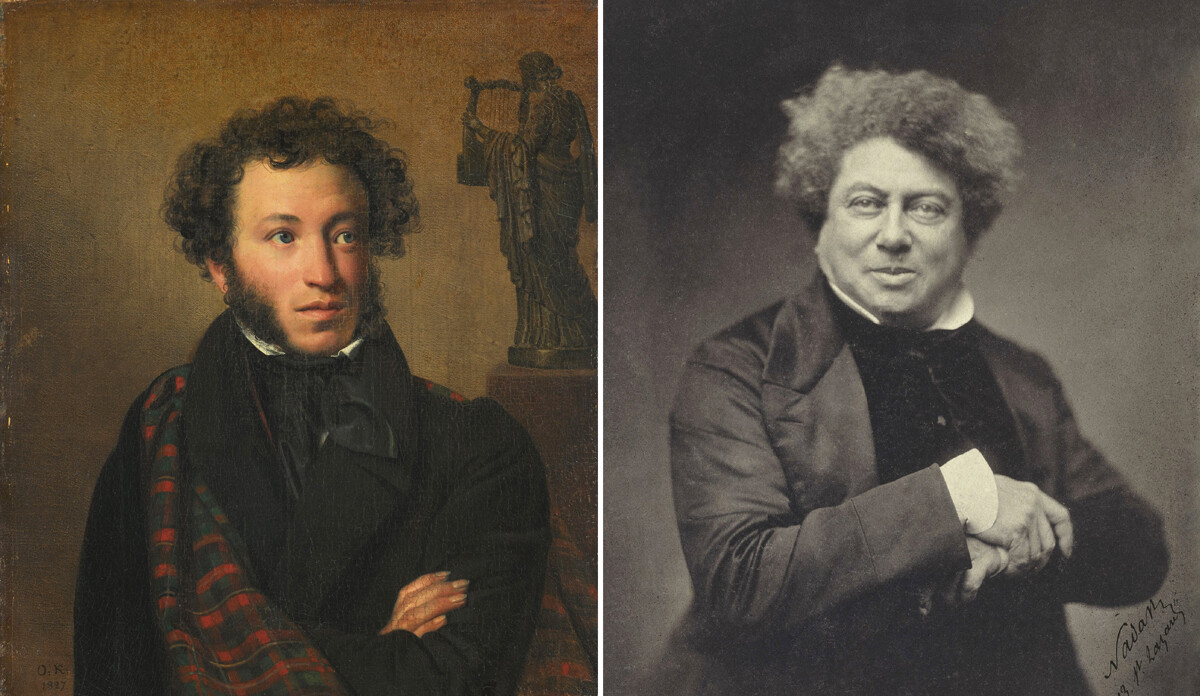

In addition, they were of almost identical age, with Pushkin having been born in 1799 and Dumas in 1802. Both found discipline and restrictions burdensome, both were passionate and impulsive and had a prodigious fondness for women and both ended up in disfavor and spent time in exile… Suffice it to look at portraits of the two writers - the resemblance is plain to see!

Peter Sokolov. Portrait of A.Pushkin / Francois Joseph Heim. Portrait of A.Dumas

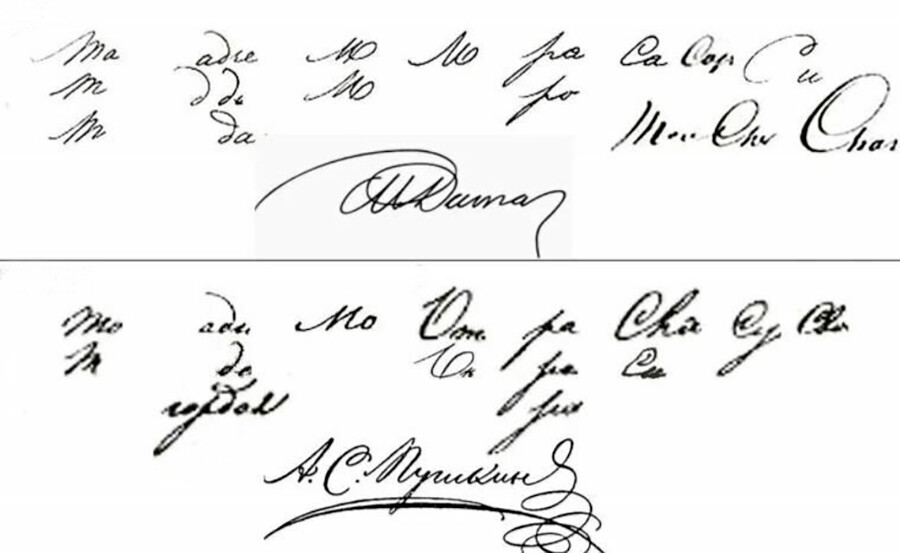

Pushkin Museum, Russia; Palace of Versailles museumThe two writers' handwriting was also suspiciously similar…

Another interesting fact supports the conspiracy theory - the name of the main protagonist in Dumas’ ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’ is Edmond Dantès (while Pushkin’s “murderer” was Georges-Charles d’Anthès). Dumas’ Dantès staged his own death and gave himself a new identity as the Count of Monte Cristo. Might this not be a hint from Pushkin (And an attempt to exonerate Georges-Charles d'Anthès, whom Pushkin fans still quietly hate)?

And in ‘Eugene Onegin’, there is a description of a duel and the death of poet Lensky because of jealousy, which fits in just a little too closely with Pushkin’s own life story.

One might add that both writers were very prolific, they were both fond of history and admirers of the Romantic Movement and both worked in a variety of genres - they each wrote dramas, novels and poetry.

All in all, if one really wanted to, one could perhaps believe that Pushkin was Dumas… But, it would then remain a mystery how in the late 1820s and early 1830s (plainly before Pushkin’s death) Dumas’ plays - ‘Henry III and His Court’, ‘Antony’, ‘Napoleon Bonaparte or Thirty Years of the History of France’ and others - were successfully being staged in Paris. And, also, how was it that during his trip to Russia no-one recognized him as Pushkin?

Orest Kiprensky. Portrait of Alexander Pushkin, 1827; Photo of Alexandre Dumas, 1855

Tretyakov Gallery; Nadar/Museum of Fine Arts, HoustonDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox