What happened to these priceless Romanov tiaras after 1917 Revolution?

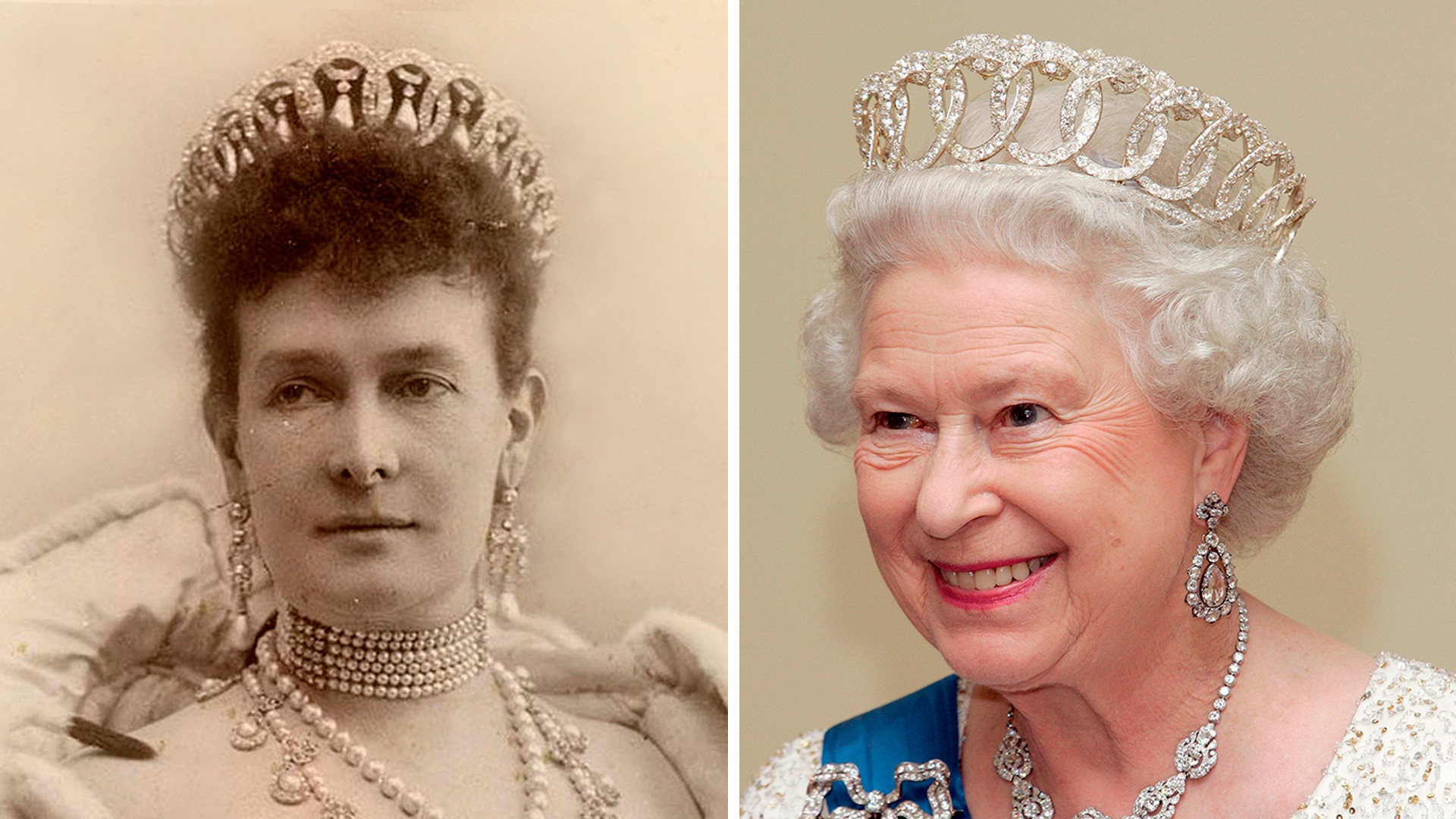

Maria Pavlovna and Elizabeth II wearing the Vladimir tiara.

Public Domain; Getty ImagesThe diamond, emerald and sapphire tiaras of the Romanov dynasty were remarkable for their beauty and opulence, and they were well known to other monarchies in Europe. This has to do with their unusual shape since most were reminiscent of the kokoshnik, an old type of Russian headdress. It was Catherine the Great who first brought the fashion for "Russian dress" to the court, and then in the middle of the 19th century under Nicholas I it was made mandatory. At official receptions, women began to wear diadems with a national flavor—“les tiares russes," as they are called abroad.

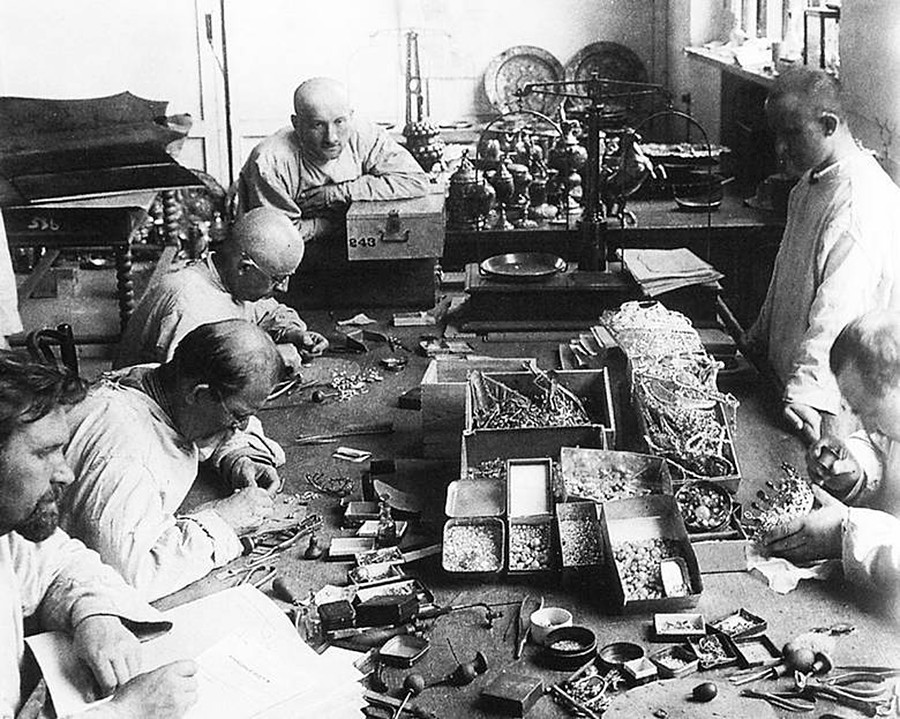

This photo shows the Romanovs' treasures found by Bolsheviks and prepared for sale.

Public DomainAdditionally, there were adaptable jewels that could be worn as tiaras or necklaces, and the pendant stones were interchangeable. This particular feature is the reason why most of the jewelry disappeared. Whatever items the tsar's family couldn't take out of the country, the Bolsheviks sold piece by piece at auctions.

1923. Bolsheviks estimate Romanovs' jewelry.

Public DomainThe Vladimir Tiara

Portrait of Maria Pavlovna in this tiara.

Public DomainGrand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia, the younger brother of Emperor Alexander III, commissioned this tiara for his fiancée, Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (later Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia), in the 1870s. The tiara consists of 15 diamond rings, each of which has a drop of pearl in the center.

Mary of Teck in this tiara with emerald drops.

Public DomainThe Grand Duchess was one of the few Romanovs who managed both to escape abroad after the 1917 Revolution and also to take her jewelry with her. Some of the treasures were taken out of the country in two pillowcases via the Swedish diplomatic mission, while a British diplomatic courier helped smuggle others across the border. These included the Vladimir Tiara, which Maria Pavlovna kept in her possession until her death in 1920. She bequeathed it to her daughter Elena, who was married to Prince Nicholas of Greece and Denmark. However, just a year later, Elena sold the tiara to England's Queen Consort, Mary of Teck, in order to improve her financial situation.

Elizabeth II in this tiara.

Public DomainIn Britain, emerald drops that can be alternated with pearl drops were made for the tiara. Queen Elizabeth II still wears the tiara today, both with pearls and emeralds, and on occasion "widowed," i.e. without either.

Elizabeth II in "empty" tiara.

Getty ImagesSapphire Tiara

Queen Marie and Maria Pavlovna in sapphire tiara.

Public DomainThis kokoshnik tiara with diamonds and enormous sapphires belonged to Alexandra Feodorovna, the consort of Nicholas I. Made in 1825, it had a matching brooch with pendants. The tiara was inherited by Maria Pavlovna, who in 1909 asked the Cartier firm to give it a more up-to-date look. She managed to get the piece out of Russia after the Revolution, although her children ended up having to sell this piece as well. Eventually, it ended up in the possession of Queen Marie of Romania—a distant relative of the Romanovs—but it no longer had its matching brooch.

Queen Marie and Ileana.

Public domainShe was rarely separated from her tiara and gifted it to her daughter, Ileana, as a wedding present. However, after the revolution in Romania that followed World War II, the royal family was banished from the country. Ileana left for the United States, taking the tiara with her, before selling it to a private buyer in 1950. The tiara’s subsequent fate is unknown.

The Pink Diamond Diadem

Grand Duchess Elizabeth Mavrikievna in this tiara during her wedding, 1884.

Diamond Fund of Russia; THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARYThe diadem of Empress Maria Feodorovna, consort of Paul I, was made in the early 19th century in the form of a kokoshnik with an enormous diamond. The diadem is set with a total of 175 large Indian diamonds and over 1,200 small round-cut diamonds. The central row is adorned with large, freely hanging drop-shaped diamonds. This piece, along with the nuptial crown, was a traditional part of the wedding attire of brides in the Russian royal family.

This is the only original Romanov diadem that remained in Russia as a museum exhibit that can be viewed in the Diamond Fund at the Kremlin. It was saved from being sold thanks to its pink diamond, which art experts deemed priceless.

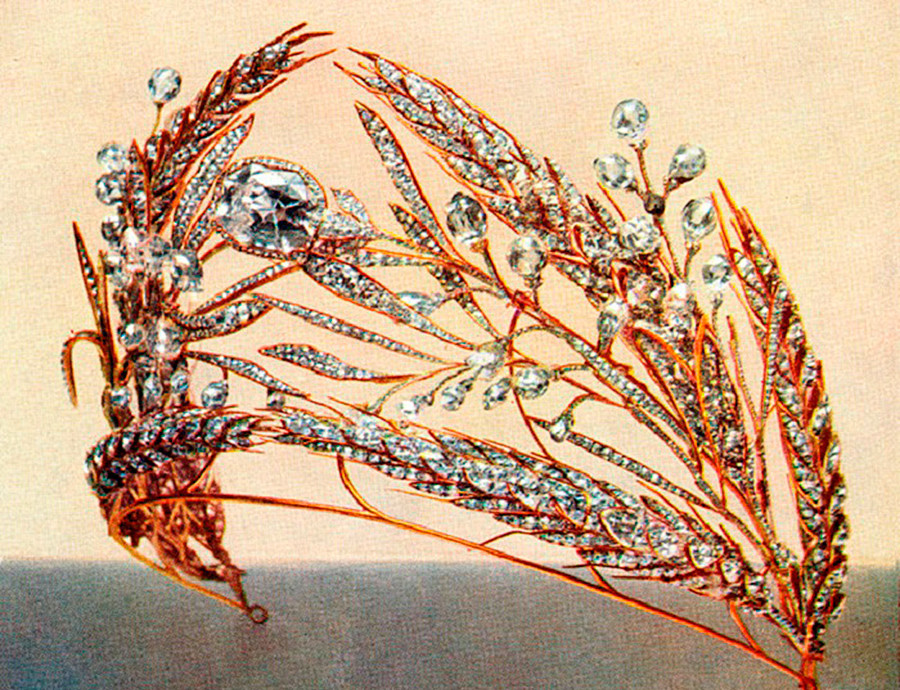

"Wheat Sheaf" Diadem

The "Wheat Sheaf". This photo was made for the auction.

Public DomainThis diadem with an original design also belonged to Maria Feodorovna. It consists of golden "flax ears" decorated with diamonds with a set a leuco sapphire (a colorless sapphire symbolizing the sun) in the center. A rare photograph of it was taken in 1927 for a Christie's auction at which the Bolsheviks sold off the Romanov jewels. Nothing is known about the diadem’s subsequent fate following the auction.

"Russian Field".

Yury Somov/SputnikSoviet jewelers made a replica of the diadem in 1980 and called it "Russian Field." It is also held in the Diamond Fund.

Pearl Diadem

The wife of Duke of Marlborough in this tiara.

Public DomainThis pearl-drop head ornament was ordered by Nicholas I for his consort Alexandra Feodorovna in 1841. After being auctioned off in 1927, the diadem changed hands among private owners numerous times. Holmes and Co., Britain's 9th Duke of Marlborough and Imelda Marcos, then first lady of the Philippines, all owned it at one point. At present, the government of the Philippines is the diadem's most likely owner.

"Russian Beauty".

Sergei PyatakovThe Diamond Fund has a replica of it, called "Russian Beauty," that was made in 1987.

Large Diamond Diadem

Alexandra Feodorovna in this tiara.

Public DomainThis large diadem incorporating a "lover's knot" motif that was popular at the time was made in the early 1830s, also for Alexandra Feodorovna. It was decorated with 113 pearls and dozens of diamonds of various sizes. It was worn by the last Empress, also Alexandra Feodorovna, when she was immortalized by photographer Karl Bulla at the opening of the State Duma.

After the revolution, the Bolsheviks decided that the diadem lacked any particular artistic merit and auctioned it off. There is no information about the subsequent owner, and the most likely theory is that it was sold off in parts.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox