7 little-known facts about Leo Tolstoy

1. Saw teaching as his vocation

Leo Tolstoy talking to peasant kids in Yasnaya Polyana

Chertkov/SputnikIn 1861, when Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, many thousands of peasants were forced to change occupation, leave for the cities, and think about how to feed themselves and their families. Worried for their future, Tolstoy converted an outbuilding of his family estate at Yasnaya Polyana into a school for peasant children, including girls.

He studied European pedagogical practice, and eventually developed his own methods. He himself taught children how to read and gave lessons on Russian history, natural phenomena, and anything that he considered important. Later, he opened several more schools in the surrounding villages. Tolstoy’s own children, as well as university graduates and admirers of the writer, also helped out as teachers.

Tolstoy encouraged children to be creative and imaginative, and greatly admired their natural curiosity and unspoilt outlook on life.

2. Loved a peasant woman

Tolstoy in a peasant robe walking in Yasnaya Polyana

O.Ignatovich/SputnikBefore tying the knot, Tolstoy let his betrothed, Sofia, read his diaries. She was shocked by the detailed descriptions of all his love affairs. Ashamed of his overactive libido, Tolstoy used his diary as a vehicle for soul-searching and cathartic self-flagellation. But what bothered Sofia most was Tolstoy’s long relationship with a peasant woman called Aksinya, who had borne him a child.

Tolstoy’s reflections on his carnal desire and “criminal” love for peasant women found voice in several works, including The Cossacks, The Devil, and Tikhon and Malanya.

Read more: Why Leo Tolstoy was a terrible husband

3. Quarrelled with the main writer of the day, Turgenev

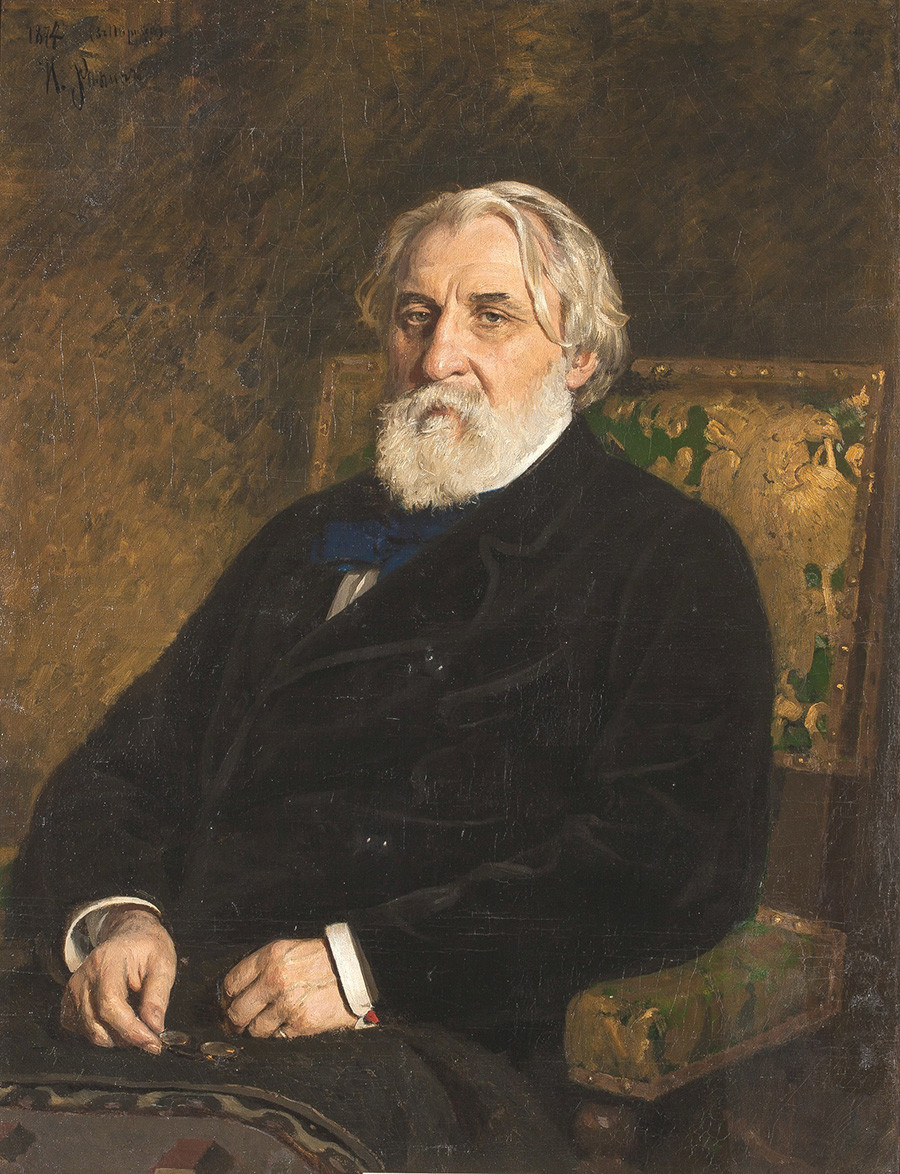

Ivan Turgenev. Portrait by Ilya Repin

State Tretyakov GalleryIn the Russian literary milieu, it was customary for established writers to patronize (in the original sense) promising debutants. Tolstoy’s undoubted talent was immediately recognized by many after the release of Childhood (1852) and Sevastopol Sketches (1855), in particular by Ivan Turgenev, who was Russia’s leading wordsmith at the time.

However, not only did Tolstoy reject Turgenev's avuncular advice, but openly criticized his unwanted patron. Tolstoy viewed European liberalism as alien, including the ideas of women’s equality in the novels of George Sand, which all “westernizers” admired.

There were also personal reasons for the bad blood between the two men. Turgenev talked openly about his extramarital affairs and illegitimate daughter, while Tolstoy simply could not accept such a “sinful” way of life (despite his own transgressions). Offended, Turgenev promised to “punch Tolstoy on the snout” — to which Tolstoy’s equally literary reply was: “Turgenev is a scoundrel in need of a good thrashing.” They reconciled only 20 years later. Already on his deathbed, Turgenev wrote to Tolstoy: “I am glad to have been your contemporary.”

4. Tried to write about the Decembrist uprising, and ended up producing War and Peace

Decembrist in Siberian exile

TASSA novel about Russia’s war against Napoleonic France was not originally in Tolstoy’s plans. His primary interest was the Decembrist uprising of 1825, when a group of noblemen staged an uprising in St. Petersburg, demanding restrictions on the monarchy and the liberation of the serfs, for which they were exiled to Siberia.

In 1856, the new tsar declared an amnesty for the Decembrists, and Tolstoy decided to write a novel about the return of the exiles from Siberia. However, he got distracted by his teaching activities (see above) and managed to pen only a few chapters. When he returned to the novel, the plot no longer seemed relevant, so he went in search of the deeper motives behind the Decembrists’ self-sacrifice — the result was the epic War and Peace.

5. Gave Dostoevsky a fit with his interpretation of the Bible

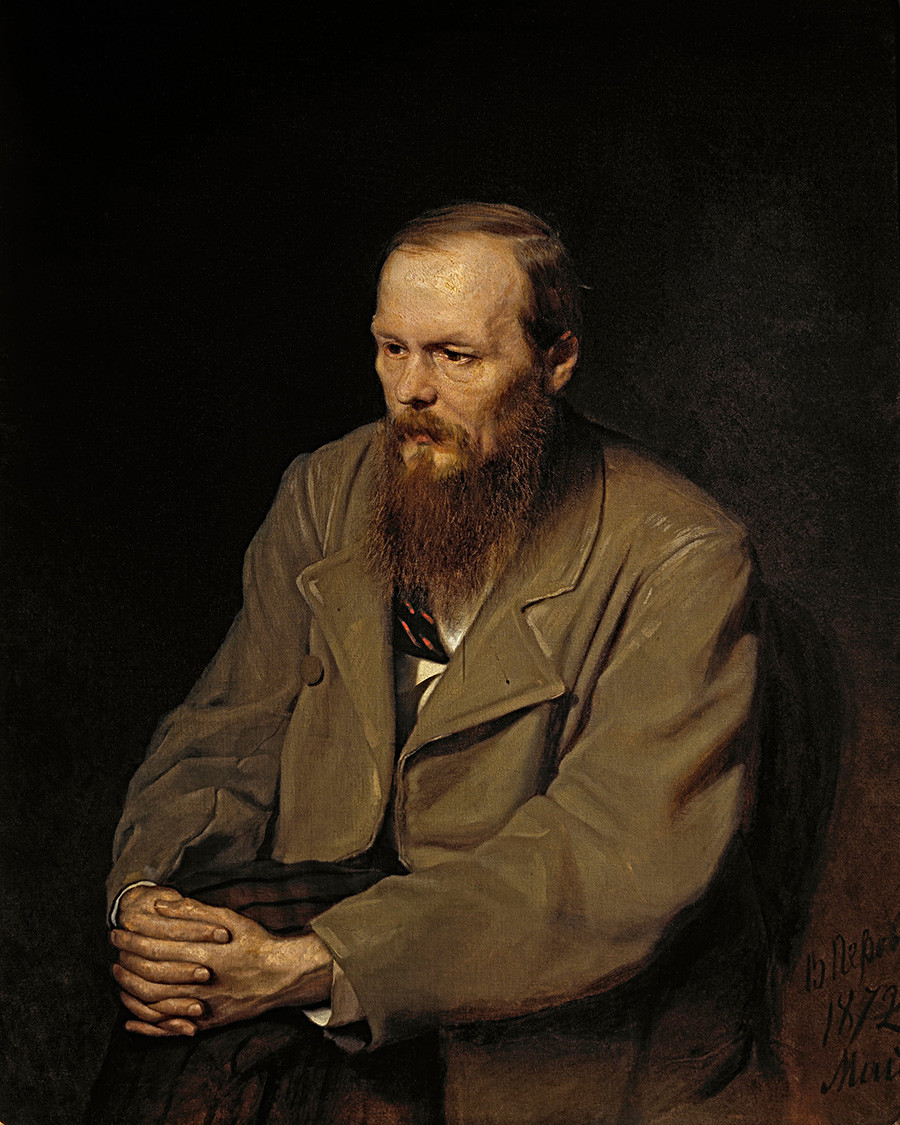

Fyodor Dostoevsky. Portrait by Vasily Perov

State Tretyakov GalleryAlthough Tolstoy was deeply religious, he had his own unique interpretation of the Gospels, believing truth to lie in the divine word, not in bowing down to everything related to Jesus. “According to Tolstoy, the teaching of Christ could be reduced to five commandments that developed or disaffirmed those revealed by Moses,” writes Andrey Zorin, author of a new biography. In brief, all people are equal (despite his views on George Sand), and adultery and violence are prohibited.

Tolstoy’s outlook interested Fyodor Dostoevsky. On meeting one of Tolstoy’s cousins, he asked her to explain his fellow writer’s ideas. She read her cousin’s letters aloud to him, after which she wrote that Dostoevsky “clutched his head in despair and cried: ‘Not that, not that!..’ He did not sympathize with a single thought of [Tolstoy].” Dostoevsky wanted to write Tolstoy a letter and start polemic, but he died.

6. Pleaded for mercy for the tsar’s killers

The assassination of Alexander II of Russia 1881 by Gustav Broling

Illustrirte Zeitung, 1881One of Tolstoy’s main ideas — non-violent resistance to evil — is reflected in his attitude to the assassins of Alexander II. In 1881, two terrorists blew up the royal carriage in St Petersburg, as a result of which the tsar later died.

Tolstoy wrote a letter to the new tsar’s reactionary administration, asking for clemency for the perpetrators as an act of Christian charity. But it was perceived as tantamount to inciting terror, and the authorities became wary of the strange writer, as they saw him.

7. Helped compile the national census

Residents of the Khitrovka district

Archive photo“In January 1882, hoping to better understand the causes of social evil and find ways to combat it, Tolstoy helped to compile the national census,” writes Zorin. The great writer worked in the Khitrovka district, Moscow’s most infamous den of iniquity, where drunkards, criminals, and prostitutes rubbed shoulders in the slums and shelters.

He mixed with the locals and gave them money, which was immediately gambled or drunk away. Tolstoy’s main takeaway from the experience was that beggars accept only minor handouts with gratitude, considering excessive generosity to be an attempt to remold them and to “thrust upon them once more the rules of the world that they have rejected.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox