5 mysterious stories involving Russia’s royal jewelry

The Imperial Russian court was one of the wealthiest in Europe. Diamonds, rubies, and sapphires glistened wildly and created an aura of superiority, something that European ambassadors and monarchs wrote about in their memoirs after being received by the Russian tsars. Russia Beyond remembers five of the most mysterious stories related to treasures from the royal treasury.

1. The Monomakh’s Cap

Monomakh's Cap, Kremlin, Moscow.

Getty ImagesThis is the oldest object of all the preserved tsarist regalia. The crown’s golden plates are decorated with more than 40 stones: Emeralds, sapphires, rubies, and pearls – and the edge is made of sable fur. The tsars supported the legend that the cap had been a gift from Byzantine Emperor Constantine to his grandson, the Prince of Kiev, Vladimir Monomakh, who ruled during the 12th century. It had originally come from Babylon, where it was found among the treasures of Nebuchadnezzar. The Kievan princes passed it on to the Vladimir princes, who in turn gave it to the Moscow princes, who united the princedoms into one nation. The concept of Moscow being the Third Rome was thus justified and the Moscow princes’ power was emphasized.

A more realistic theory says that the cap, which follows central Asian headdress in form, was made at the turn of the 14th century by Asian masters and gifted to Moscow prince Ivan Kalita for his loyalty by Khan Uzbek of the Golden Horde. From then on the “golden cap” was always bequeathed from father to oldest son. The Russian tsars wore it only once during their lives: When they were crowned. It was last donned in 1682, at the coronation of Ivan V.

2. The Orlov Diamond

Imperial scepter made for Catherine the Great in the early 1770s. Topped by the Orlov diamond and a gold cast double-headed eagle.

Yuriy Somov/SputnikThroughout most of the 18th century Russia was ruled by women, and during this time the empire’s court really shined, literally. Catherine the Great was known for her love of jewelry. It’s no wonder that during her reign the Russian court came to possess one of the most famous stones in the world, the Orlov Diamond, which in 1774 became part of the royal scepter.

According to legend, the 189.62 karat stone was given to Catherine by her lover, Grigory Orlov. Another theory claims the empress secretly bought the stone herself with money from the royal coffers.

Catherine the Great holds the Imperial scepter. Portrait by Alexei Antropov, 1765.

Tver Art GalleryThe diamond was found in the mines of Golkonda, India in the 17th century and was first owned by the Great Mughals. In the middle of the 18th century Persian ruler Nader Shah captured Delhi and took the stone along with other treasures. It was then embedded in the eye of the Ranganatha deity statue in a Hindu shrine, but was stolen by a French soldier. He had converted to Hinduism to carry out the heist and served in the shrine until winning the trust of the Brahmins. Thanks to the Frenchman, the diamond appeared in London where it changed hands several times before winding up in the collection of Catherine the Great’s jeweler - Ivan Lazarev, who sold it to the empress.

3. The Shah Diamond

The Shah diamond, one of the Seven Historic Gems of the Russian Diamond Depository.

Yuriy Somov/SputnikAnother unique diamond appeared in Russia due to more tragic and bloody circumstances. In 1829 a Persian prince brought it to Tsar Nicholas I as compensation for the destruction of the Russian Embassy in Tehran, and the murder of Alexander Griboyedov, diplomat and author of Woe from Wit.

The large 88.7 karat diamond is not faceted, just polished, and the groove in the narrow part proves it was worked on by a master.

Alexander Griboyedov. Miniature.

SputnikThe story began in an Indian mine in the middle of the 15th century. The names of the rulers who owned it in various periods are carved into its three facets: Nizam Shah (who called it “Allah’s Finger”), ruler of the Great Mughals Jahan Shah, and the Persian Fath Ali Shah). Strangely, each time a name was carved, wars and turmoil followed and the diamond swapped hands. The last name was etched into it in 1824, after which the shah’s army was obliterated in the Russian-Persian War. In accordance with the peace treaty, the territory of eastern Armenia was given to Russia and the shah had to pay the Russian emperor 20 million rubles in silver. And although the diamond is famous for being compensation for the blood of a Russian emissary in Teheran, historians believe the emperor received it as an indemnity payment.

4. The Vladimir Tiara

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna wearing the Vladimir Tiara.

Aniklot PazettiThe history of the diamond tiara with the drop-shaped pearls, which is often worn by British monarch Queen Elizabeth II, began in the Russian Empire in the 19th century. In 1874 Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, younger brother of Emperor Alexander III, gifted it to his bride Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin for their wedding. It was made by court jeweler Carl Edvard Bolin and it became known as the Vladimir Tiara, named after the client.

Queen Elizabeth II wearing crown, blue sash and pink gown.

Library and Archives CanadaAfter the Revolution the grand duchess was hiding in Kislovodsk and by some miracle, thanks to the help of English diplomat and antiquarian Albert Stopford, was able to take her money and jewels from the St. Petersburg cache before sneaking them out of Russia in 1920. After the duchess’ death her daughter sold the jewels to English Queen Mary of Teck, consort of King George V. So Elisabeth II inherited the tiara from her grandmother.

5. The last empress’ jewels

Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna.

Library of CongressEmperor Nicholas II’s wife, Alexandra Fyodorovna, owned a magnificent collection of jewelry. She had unique objects such as a Faberge brooch in the form of a tea rose with colored diamonds, and a two-meter lance made of perfect pearls the size of grapes. When in 1917 the Bolsheviks moved the royal family to Siberia, the empress and her daughters took some of the jewels with them, hiding the necklaces under their clothing, replacing buttons with diamonds, and sewing everything else into the lining of hats, velvet belts, and undergarments. After the family was shot all the jewels were taken by the Bolsheviks.

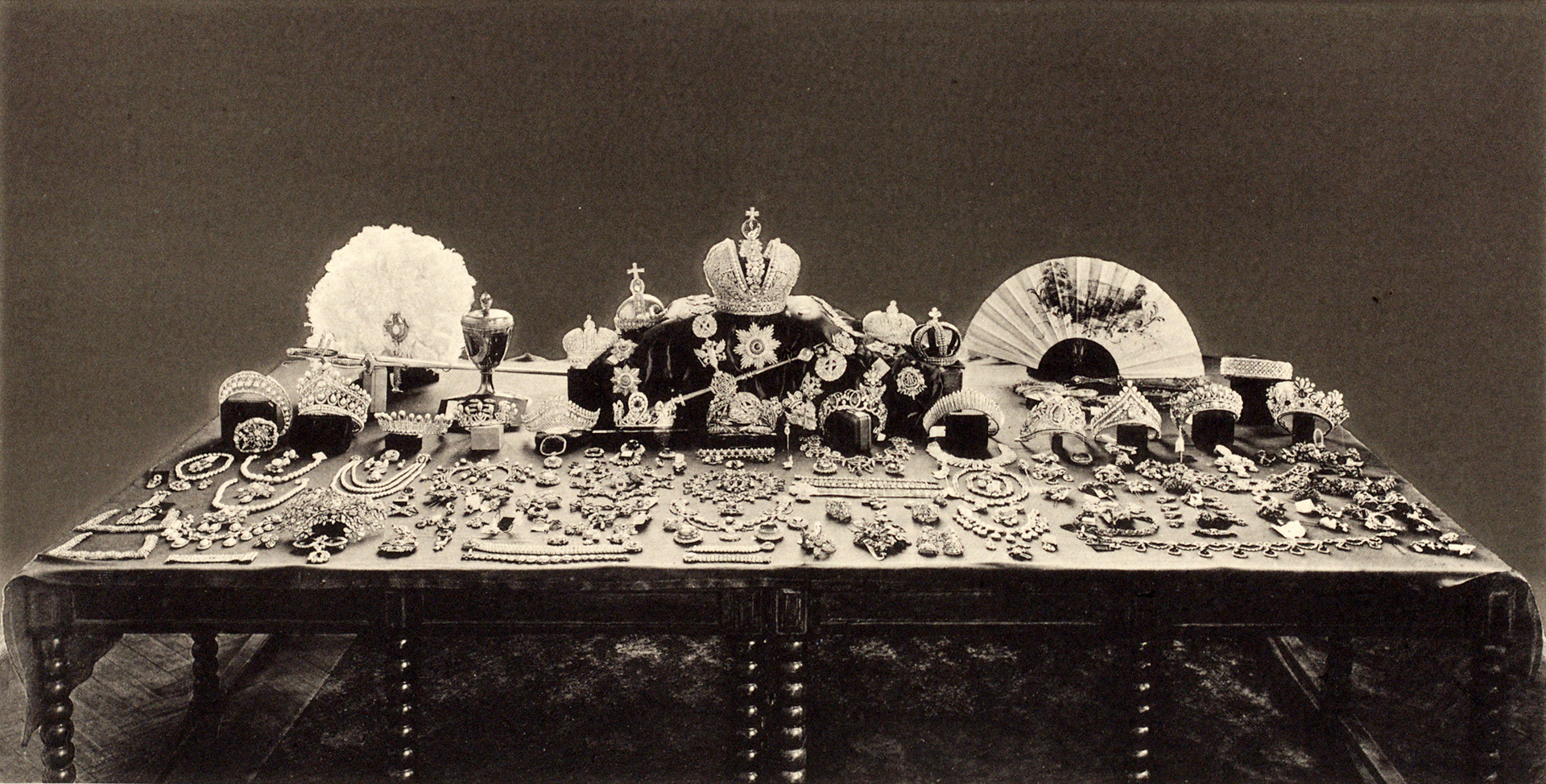

This photo, taken in 1925, shows the entire Russian jewelry collection.

USGSFrom 1925 to 1926 an illustrated catalogue of the diamond treasury was published. It included the royal jewelry and regalia. The four-part publication was translated into the main European languages and was distributed among potential buyers. In October 1926, a representative of an Anglo-American syndicate - Norman Weis - bought almost 10 kg of the royal jewels, paying only £50,000 pounds. He sold some of them to Christie’s, but auctioned the main masterpieces at the Russian State Jewels auction in London in March 1927. Among the 124 lots there was an imperial wedding crown, a diadem with ears, and Catherine the Great’s ruby port bouquet.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox